Intermoney | US inflation beat expectations, stabilising at 2.1% year-on-year in January. It meant our estimates and those of the bulk of the consensus were wrong to glimpse a brief respite in the upward trend in prices at the start of 2018. So the problem is not this issue, but the fact that the market will end up putting even more emphasis on the possibility of seeing inflation rates higher-than-expected months ago. And, unfortunately, this will continue to spark potential over-reactions which would give way to strong, quick movements.

There are the ingredients to fuel this possibility, given that the advances in the prices of health goods and services are starting to pick up again and the year-on-year rises of 1.6% last September should be considered as their lows (2.0% year-on-year in January). Whatsmore, in the spring, we will stop seeing the draining affect which the huge cut in mobile phones had on prices’ statistics. Therefore anyone who wants to look for figures to generate a buzz about inflation will find them, and will also be supported by the Cleveland Fed’s predictions.

On February 14, the aforementioned predictions put the US CPI year-on-year rate for this current month at 2.18%, with the central PCE at 1.57%. Predictions in some areas of the market due to their origin, in spite of the fact that the day before the publication of the last US CPI figure, they were in line with consensus, up 1.94% from a year ago. An increase which is not a criticism of the Cleveland Fed’s valuable exercise, but more of a reminder that all prediction exercises are subject to a certain degree of error.

The institution itself acknowledges the previous question, particularly in the first months of the quarter, when the mean squared error for its quarterly forecasts was 0.4% for the central PCE. In fact, with a 70% probability, they estimate that the aforementioned central PCE will be betweeen 2.0% and 2.8% quarter-on-quarter in Q1’18. That said, as we mentioned above, there are reasons to expect more from US Price indices in the coming months. And, if the markets’ fears increase, we could see the Cleveland Fed’s estimates gaining prominence, with its forecast for a quarterly CPI of 3.44% and central PCE of 2.48% in Q1’18.

At this point, we should not lose sight of another matter, namely the fluctuactions in crude prices, which generates a lot of noise in inflation statistics in the short-term and goes head to head with the dynamism of unconventional hydrocarbons. Something which should curb prices and serve to offset some of the aspects mentioned above.

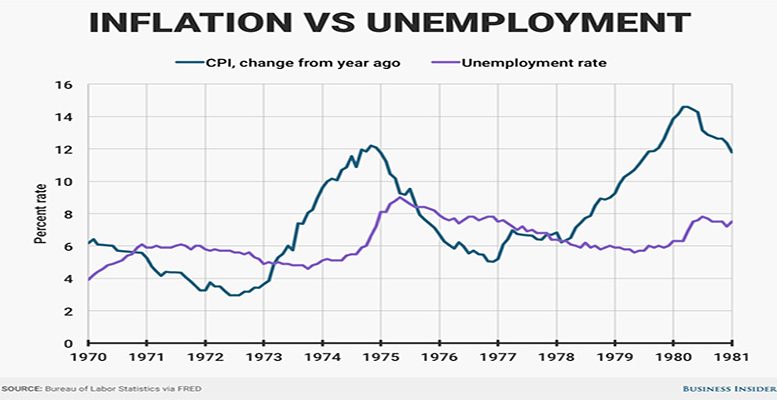

However, as usually happens during the most intense moments in the markets, there will be those who take advantage to make something of an impact and bring back concepts like stagflation, as also happened with the forgotten “helicopter money.” Without getting into long expectations which we will leave for another time, it’s simply worth mentioning the definition of stagflation contained in the macroeconomic manual of Dornbusch-Fischer: “Stagflation is a term which was coined to refer to high unemployment (“stagnation”) and high inflation.” This was a situation which occurred in the mid-1970s and in the turn of the decade of the 80s, under the shadow of the oil crisis. For example, in the US, the jobless rate reached a maximum 10.67% in 1982 and the CPI was 14%.