Intermoney | The unexpected resignation of Japan’s Prime Minister, Shinzo Abe, puts an end to the mandate of the longest-lasting head of government in the country’s history. However, it leaves behind an unfinished legacy and a country in recession. Abe’s resignation is not good news as it comes at a critical economic, political and social time. Despite living with the effective policy carried out to contain the evolution of the pandemic, it is important to consider the mixed results of his economic policies.

In 2013, Abe announced an ambitious and aggressive political plan of economic reforms to pull the country out of the long period of deflation in which it found itself. The policy, called Abenomics, was based on a three- lines strategy to boost domestic growth. The “three arrows” of the policy were: fiscal stimulus worth JPY 10.3 trillion for infrastructure spending such as roads, buildings and bridges; monetary easing to help increase liquidity in the economy, and structural reforms to boost private investment. Seven years later, the impact of the ambitious measures has been mixed.

The resulting economic momentum was fuelled by the weakness of the yen, which stimulated exports, corporate profits and the stock market. However, this momentum soon faded as the ability to address old structural problems became weaker. So inflation has continued to be a headache, while wages have not risen as strongly as expected. And all this without taking into account the problems of an aging population. The country continues to suffer from labour shortages due to the contraction of the work force. Efforts to increase the birth rate through childcare services, parental leave schemes and monetary assistance in the form of child allowances have also not had the expected result.

The lack of depth in Abe’s efforts is evident in the insufficient dynamism of the macro references, despite the encouragement of the effects of the pandemic. In this regard, labour market data will show an increase in the unemployment rate (3%), with fresh highs in COVID-19 cases recuding new job offers in the service sector and particularly in the areas of entertainment and tourism.

Last week, data released continued to point to a fragile recovery in Japan. Notwithstanding, it is true that the monthly performance of industrial production in July (8.0% m.) was surprising thanks to the good performance of vehicles and their components. However, the year-on-year rate continues to indicate that the manufacturing sector’s recovery is still far off. On the other hand, retail sales fell for the third consecutive month (-3.3% m.), emphasising the still worrying trend in private consumption.

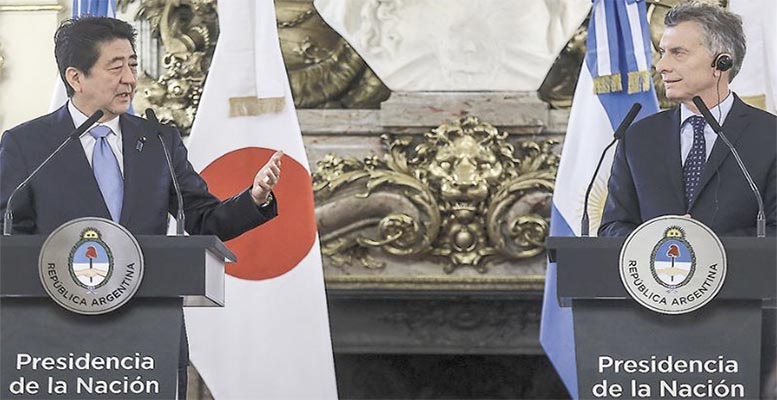

Along with Japan, there are other economies destined to live “Groundhog Day,” due to government decisions where past mistakes have been repeated. One of these nations is Argentina, which last week wrote another chapter in its abrupt economic history, although this one was positive. The country managed to successfully close the restructuring of its debt in dollars with private creditors. About 93.5% of Argentine bond holders accepted the government’s offer after over four months of negotiation. Up to 99% of the creditors are voluntarily bound and so only 1% are left out of the agreement. Then investors holding 99% of the 65 billion dollars in international bonds in the country will exchange their securities for new promissory notes. The agreement delays the maturity dates of the bonds and cuts interest rates by more than half, giving the country oxygen.

However, this relief in terms of international creditors is the first step in a long road in which Argentina will have to recover its financial equilibrium and guarantee an economic recovery over the next years. Macri’s arrival in power led to betting on public debt with foreign countries in order to avoid printing debt in pesos. The problem is that the bulk of the new debt was issued in hard currency, falling back into the well-known “original sin.” Emerging and developing coutries have recurrently had to face the negative consequences of this.

The government’s foreign debt has gone from $89.323 Bn in Q2’15 to $170.296 Bn in Q1’20, which is equivalent to an increase of 90% or $80.973 Bn. This government debt has been a key factor in the increase of Argentina’s foreign debt, also explaining 62% of its aggregate rise from end-2015 to a total of $274.247 Bn at the beginning of 2020. This situation contrasts with the $72.340 Bn in non-financial corporations and households’ debt, where the increase has been much more moderate.

Then Argentina’s problem continues to be the strong growth in the government’s foreign debt, mostly in foreign currency. The restructuring is very good news and should serve as an incentive for generating confidence. And, above all, with a view to 5 years from now, when it will have to face higher debt maturities. Argentina still lacks a credible medium-term fiscal and monetary policy plan and a lot has to happen here to get its economy back on track.