Throughout this time, anecdotal and hard evidence have suggested the “Japan trade” has been mainly driven by non-Japanese investors, rather than the Japanese. This begs some obvious questions. Why have Japanese investors not participated in the trade? Will they eventually participate? If they do, how will this affect Japanese asset prices and the currency?

We attempt to answer these questions using an empirical analysis of the optimal asset allocation for Japanese investors and find three key takeaways. First, it should not come as a big surprise that Japanese investors have not participated in the Japan trade. Second, the shifting inflation dynamics in Japan suggest a potentially big change in the optimal equity-bond mix in Japanese portfolios. Third, when a shift does happen, the implications for relative asset prices should be large.

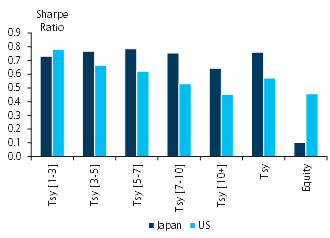

The first question we address is why Japanese investors have been slow to embrace the rise in equities and decline in the yen in their portfolios. Figure 1 looks at the Sharpe ratios of holding equities and various maturities of government bonds over the near 20 years of Japanese deflation, including Japanese and US markets.

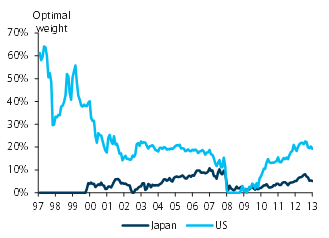

The message is reasonably clear. In a deflationary environment like Japan’s a large overweight in fixed income – especially in the longer end – made sense. In a more ‘normal’ inflationary economy like the US, equities fare much better. Figure 2 looks at a rolling, in-sample optimal allocation for equities for Japanese and US portfolios. Again, the message is that the Japanese have been quite rational in their decision to underweight equity during the past 20 years. It probably also helps explain why they have been slow to jump into equity markets today, especially after so many false starts in Japanese equities over the years.

The second question we ask is whether Japanese investors will shift their portfolios away from fixed income and toward equity. Our empirical analysis suggests they will. Figures 1 and 2 examine Sharpe ratios and optimal bond-equity allocation, conditioned on 12 month forward inflation being above and below median levels. We also include the US Sharpe ratios and optimal allocation conditioned on above-median inflation.

The picture is again clear. Even in Japan’s deflationary era, episodes of above-median inflation indicated a much higher weight for equities in the optimal asset allocation. If Japan manages to become more like the US in its inflation outcome, the optimal balance will swing even more in favour of equity. Net-net, assuming even modest success in generating higher inflation levels, the optimal allocation for Japanese investors will shift notably away from fixed income and toward equity and other risky assets.

A final question is whether an asset allocation shift by Japanese investors will have a meaningful impact on relative asset pricing. We think it will. Figure 2 shows total Japanese pension allocations and the government pension (GPIF) allocation compared with other countries. It also shows the GPIF advisory panel recommendations for allocation shifts. Assuming these recommendations are adopted, the relative allocation shifts would amount to a sizable $160bn.

If the whole Japanese pension industry undertook a similar shift, the numbers would be closer to $400bn. Given that Japan’s national wealth is generally overweight fixed income, a continued rise in inflation could easily imply rather large asset allocation shifts accompanying big changes in relative prices.

Be the first to comment on "The Japan macro trade: Watch Japanese investors in 2014"