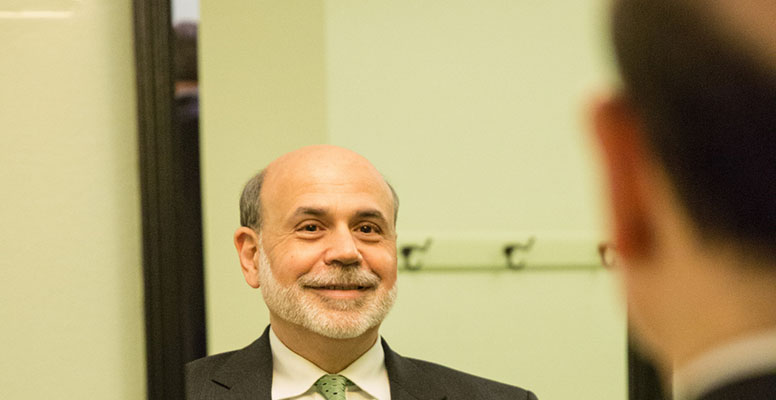

When the former Chairman of the world’s main central bank, the man credited with saving the global economy from a 1930s style depression, starts talking about cartoons it doesn’t seem very serious. But Americans … you know what they are like.

After all, no-one could imagine the Governor of the Banco of Spain with a trolley in the supermarket, dressed in a pin-striped suit which emphasised – as if it were needed – the similarity of his build to Homer Simpson.

And curiously this sight could be seen when Ben Bernanke was Chairman of the Federal Reserve, while his wife – a fan of flamenco and the films of Carlos Saura – was putting in the trolley the products that the leader of global monetary policy was no doubt going to happily wold down. All of this and more used to happen in the supermarket of the Whole Food chain (which Amazon bought for 13.4 billion dollars or 11.4 billion euros last year) on P Street in Washington.

Since leaving the Fed, according to colleagues at the think tank Brookings Institute, Bernanke has lost a lot of weight, although he hasn’t lost his hostility to human beings in general. This may be why on the few occasions he speaks – which is even less if you only count when he does so in public, which makes him feel physically sick – he resorts to metaphors. It is what he did in May when he declared that “in 2020 the coyote is going to leap off the precipice and is going to look down”.

Bernanke was referring to Wile E.Coyote, the coyote in the Roadrunner, a series of Warner cartoons which ran in the 50s and 60s. One of the most repeated gags in the episodes (in which the coyote not only failed to catch the Roadrunner, but always ended beaten up) consisted in the poor beast leaping off a precipice and continuing to run in the vacuum, until at some point he looked down and realised he was in the air. The end of the story can be imagined by any reader less than 35 who didn´t watch these cartoons as a child (you can also watch them in YouTube, whose peculiar idea of intellectual property rights undoubtedly allows you to post these and other cartoons whether or not you hold the copyright).

In any case, according to Bernanke, the US economy is heading towards recession in two years. The reason, from a macroeconomic point of view, is that the imbalances accumulating in the world´s leading economy are making the current rate of growth unsustainable. On the one hand, unemployment not only does not exist, but the growth of the labour market is such that people who had given up looking for work are reincoporating themselves into the labour forcé because they are finding opportunities they never thought they would have. At some point this has to translate into an increase in wages which will oblige the Federal Reserve to accelerate the increase in interest rates. Even more so because – and this remains unexplained – productivity remains sluggish.

Moreover, the increase in prices is supported by an unexpected factor: the trade wars that the Trump administration has opened with practically the whole world in a series of sectors key for companies´supply chains, like software and steel (curiously the textile sector has been unaffected by Trump, which allows Jael Kushner – better known by her maiden name, Ivanka Trump – to continue importing from China the shoes she sells in the US). Tariffs always mean an increase in prices, and even more so in an economy already functioning at the limits of its productive capacity.

In fact, if the US persuaded the EU and China to further open their markets to its goods and services, it would have a problem, because it could not cope with the presumed increase in demand this would bring. It is clear that increasing exports is not the objective of Donald Trump and his two principal advisors on international trade, Peter Navarro and Robert Lightizer. Their ideal is autarky, in other words, the end of international trade. That is, also, a factor that works in favor of the exhaustion of the expansionary cycle: the closure of the US economy to the rest of the world.

There are indeed market signs that the expansionary phase is coming to an end. The most obvious case is the yield curve, which in recent months has flattened until the difference between two year and ten year bonds has fallen to 27 basic points, which in principle constitutes a clear indicator of recession and a complication for monetary policy. In fact the last time the yield curve was so flat was in 2007, when the sub prime mortgage crisis was, literally, about to begin.

However, there are other indicators showing no concern about medium term expectations for the economy. The clearest example are equity markets. Although so far this year the índices of the largest companies – the S&P 500 and the Dow Jones – have not only not risen but on occasions approached technical correction territory – which is when they fall at least 10%, the Russell 2000 index, which brings together SMEs, and the tech heavy Nasdaq have continued to rise. This seems to show that investors continue to bet on the internet companies which have moved the markets in the last 18 months, and for shares in companies less exposed to the vagaries of trade policy. Even more significant is the fact that defensive sectors – like electricty companies, food, consumer goods – have been abandoned en masse by investors.

That fixed incomes suggest a recession while variable incomes suggest an expansion is not new. This also happened in 2007. Wall Street is in the second largest expansion in its history, after that which began in November 1987 and ended in March 2000. The same can be said about the growth in the S&P 500. And the big companies have no seen improvements in their share prices not only because of trade tensions, but also because the market has discounted the impact of the benefits of the December tax cuts and because those benefits, and the repatriation of capital that many companies have outside the US, have been destined for treasury or dividend payments.

In other words: all the good news has been discounted. And among it, and in a very special way, that the US will grow at 2.9% this year. That the fiscal stimulus will end in the second half of 2018 has also been discounted. What should happen next is an adjustment of expectations. And, with it, a posible recession. Either that or Donald Trump Will cut taxes again and the US, like the coyote, will continue to run in space.