A number of entrenched nonmarket-based property policies — such as restrictions on home purchases, sales and prices — are key hurdles to making timely policy adjustments.

But since the property sector plays such a crucial role in China’s growth, we believe Beijing will eventually ease many of the tightening measures in large cities during or after the spring of 2019. It is only after this that growth might recover, and thus our views on the property sector are quite crucial to accurately predicting the bottom of the ongoing growth slowdown.

Prepare for a frigid winter

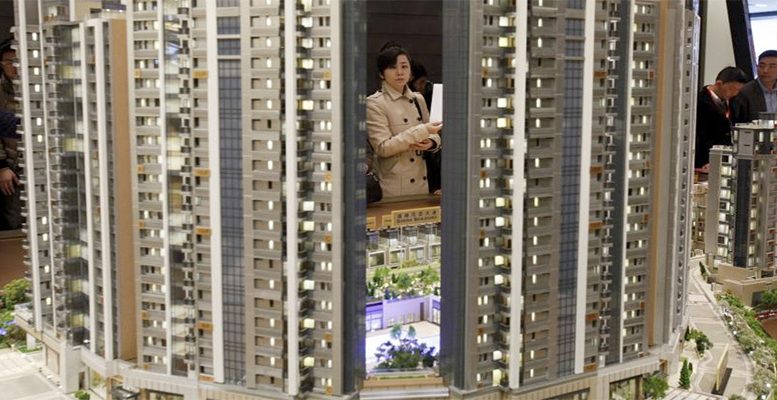

The property market boom since mid-2015 is finally showing signs of losing some steam, and the cooling property sector appears set to become a further drag on China’s economy, amid a potential escalation to a full-blown trade war with the U.S. and domestic financial fallout following the rapid expansion of credit from 2015 to 2017.

The situation could worsen significantly before improving. We expect new home sales, in terms of floor space, to plummet by more than 10% on an annual basis and property investment growth to drop into negative territory during some months in 2019. Infrastructure spending could weaken on slowing land sales, while property-related financial assets could take a significant hit.

Some special factors could make the coming winter for the property sector especially frigid relative to previous down-cycles.

First, the “long-term mechanism” is composed of extremely interventionist policies that are mostly antithetical to market forces, such as outright price controls. At the 19th National Congress of the Communist Party of China in October 2017, the party leadership highlighted the essential theme of this “long-term mechanism” as “housing should be for living in, not for speculation.”

These tightening measures, which have been imposed on large cities since late 2016, have become increasingly intrusive and are a disservice to China’s urbanization objectives. However, because these interventions have been branded as part of the “long-term mechanism,” it has become politically challenging for governments to extricate themselves from these nonmarket-based policies.

Second, despite the easing of credit conditions, it will be increasingly difficult for developers to obtain funding in the coming months. The Pledged Supplementary Lending-backed (PSL-backed) cash settlement of shantytown redevelopment projects is unlikely to be sustained forever. (Editor’s note: This program pays compensation to residents whose homes are demolished.) Offshore funding will become increasingly hard won and will become much more expensive due to the U.S. Federal Reserve’s policy rate hikes. Onshore funding will also become more challenging to find as bond repayment pressures rise rapidly.

Slowing new home sale growth will make obtaining funding from presales challenging. The sharp gap between new home sales and home completion also points to a potential funding shortage for developers.

Third, even without a tapering PSL, new home sales in small cities that benefitted from the PSL will lose steam as households use up their savings and take on too many mortgage loans. Simply put, the boom in small cities will be over soon, regardless of the pace of PSL issuance in the coming months.

How will Beijing ease previous measures?

By the spring of 2019, when we expect new home sales growth to nosedive and GDP growth to sink, we believe Beijing will likely not only cut the down-payment ratio and lower mortgage rates, but also make large adjustments to its “long-term mechanism” by scrapping most of its nonmarket-based tightening policies, such as home price controls, restrictions on reselling homes and restrictions on home purchases.

We also expect Beijing to gradually taper the PSL-backed cash settlements for shantytown redevelopment projects, while introducing more market-based mechanisms to increase land supply to big cities with population inflows.

To be sure, we are strongly against a simplistic easing of previously imposed restrictions, and we do think cities should allocate some resources to providing housing for the poor and the young.

However, we think it is very important for China to recognize the role of large cities, to let markets play a major role in allocating homes and land, and to give migrant workers more access to public goods and rights to dispose of their lands (at least their residential lands) in villages. If Beijing wishes to continue subsidies like the PSL, there should be a more transparent mechanism to distribute funds to cities that absorb the most migrant workers and talent.

By significantly increasing residential land supply to those growing cities and incentivizing local governments to maintain stable home prices by adding home supply, we believe easing restrictions will not necessarily increase home prices or lead to another property bubble.

Lu Ting is chief China economist at Nomura International (Hong Kong).