Katherine Davidson (Schroders) | More than 114 million people lost their jobs over 2020, according to the International Labor Organization. Even more saw their working hours and wages cut.

The worst affected industries were accommodation and food services where global employment declined by over 20%, followed by retail. These sectors were particularly hard hit by lockdowns, forced closures and plummeting tourism. Women and younger workers were badly affected.

You could be forgiven, then, for thinking there’d be a mad scramble for jobs when global economies perked up and the High Street reopened. But what we’re actually seeing is a labour shortage in some areas of the market, which is pushing up wages.

What’s behind the labour shortage?

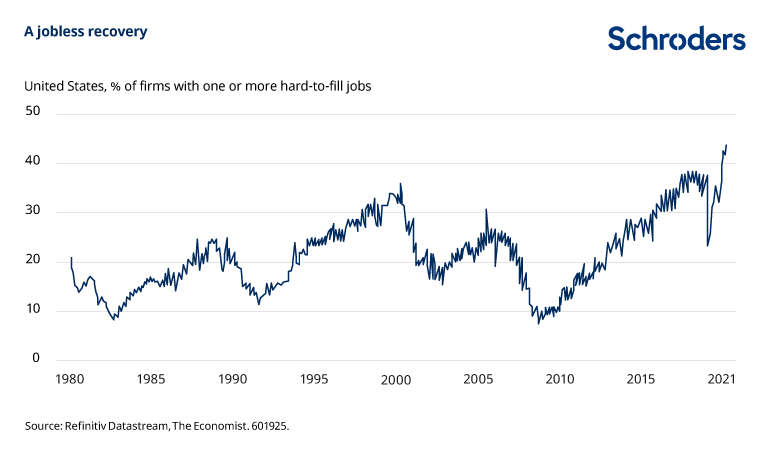

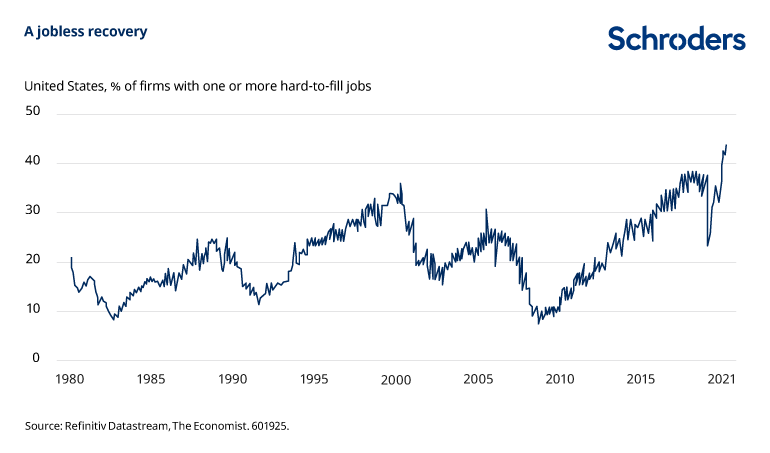

In the US, almost half of American companies are finding it difficult to fill one or more jobs (see chart below). It’s a similar story in the UK where firms also report they’re struggling to fill vacancies.

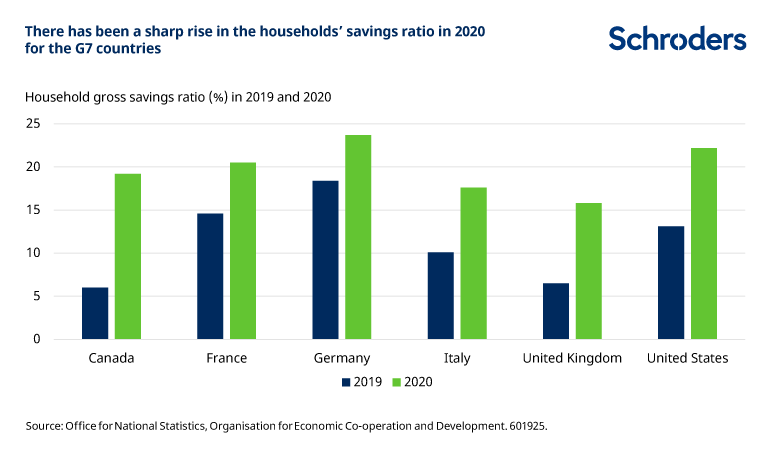

The lifting of lockdown has resulted in surging consumer spending, as re-opening excitement coincided with strong household balance sheets after a year of forced saving. The below chart shows just how much additional saving households managed to squirrel away in 2020 compared to 2019.

Consumers have been particularly keen to splurge on leisure and experiences to make up for lost time and revive their stagnant social lives. Businesses that have been essentially shut for the last year have struggled to accommodate the sudden rush of demand, especially as remaining Covid-19 measures like table service and extra cleaning increase labour intensity.

As vacancies go unfilled, companies are resorting to unusual methods to attract workers. One McDonald’s restaurant in Florida is offering $50 to those who turn up to job interviews. Surprisingly this hasn’t made much difference to this recruitment drive. Others are offering sign-on bonuses and rewards for referrals with varying degrees of success.

Where are all the workers?

There are no fewer potential workers than there were before the pandemic, so this is a bit of a puzzle. To some degree it’s a transitory issue due to sudden reopening and the time and admin required to fill vacancies (known by economists as ‘frictional’ unemployment).

Plus, these sectors disproportionately employ younger workers, who may be more reluctant to return to crowded workplaces before they’ve been vaccinated. As vaccination rates among younger cohorts accelerate this issue should ease.

It also seems as though some of the older cohort have brought forward their retirement, given lower participation rates among the over-60s. Anecdotally, the pandemic has caused all of us to reassess our priorities and many people will have vowed to spend more time with loved ones once they are able. Those who are financially comfortable may well have decided to retire early or – for workers of any age reduce their hours.

More cynically, generous support payments could also be putting people off returning to work. It’s reported that many minimum wage workers can earn as much by collecting pandemic unemployment insurance as they can by working.

In the UK, Brexit has resulted in a much-decreased pool of migrant labour. It’s estimated that as many as 1.3 million overseas workers have left British shores since late 2019.

Migrant workers were disproportionately concentrated in – you guessed it – hospitality, so this is aggravating labour shortages. While some of the factors above may be temporary, this will be a permanent problem. Some in the industry, even ardent Brexiteers, have now started to lobby for new migration schemes.

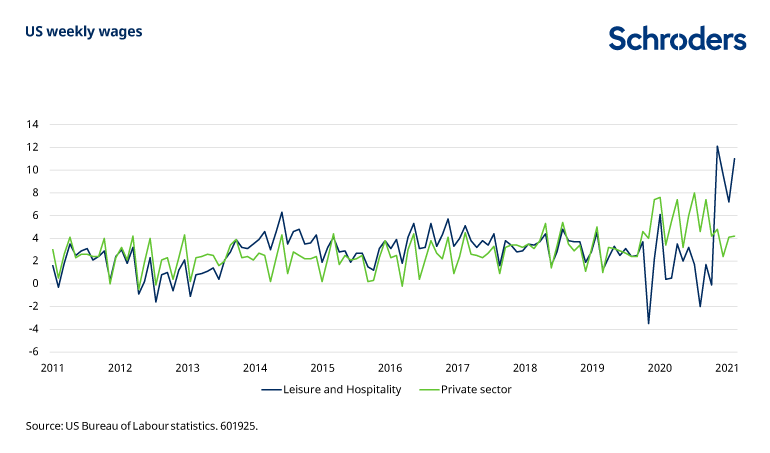

Wages are rising in response

Economics 101 dictates that when demand exceeds supply, prices (i.e. wages) will rise. This should redress the balance by attracting inactive workers back into the labour force, and/or dampen demand as wage inflation is passed on in higher prices for meals and hotel stays. Indeed, there’s evidence both in the UK and US that this is happening, particularly in the retail and hospitality sectors.

Rising wages feed through into wider inflationary pressures and are of particular interest to economists (and investors) because they may drive a ‘wage-price spiral’ whereby workers bargain for regular wage hikes to cover rising living costs. Also, unlike most prices, wages are what economists call ‘sticky downwards’ meaning that they very rarely fall even in weak economic environments.

The silver lining

But wage inflation is not all bad news, especially for sustainable investors. For a start, the flip side of higher costs for businesses is more money in the pockets of workers. Low paid workers typically have a high marginal propensity to spend, so most of the money will end up being pumped back into the economy. Businesses that cater to these workers will end up net-net better off.

Secondly, higher wages tend to make for happier workers, which can boost productivity and retention. This is why we’ve tended to favour companies that already pay above the minimum wage, as well as because they will see less cost pressure when the wage floor rises. Companies that have not valued their workers have the highest risk of losing their staff once they have other options.

The new social contract

Wages are, of course, only one element of an employment package: the past year has also increased the value placed on wider benefits such as healthcare, childcare and sick leave.

‘Gig economy’ firms (i.e. those that use short-term contracts or freelancers rather than permanent workers) such as Uber and food delivery services have come under increasing pressure from regulators and investors to provide proper benefits for their staff.

High profile UK investors recently boycotted the Deliveroo IPO (initial public offering, i.e. listing on the stock market) due to environmental, social and governance (ESG) concerns. On the other hand, most companies now see post-pandemic flexible working options as essential for recruitment and retention.

Since the start of the pandemic, we’ve written about our belief that a new social contract is emerging, particularly in relation to how employers treat their employees. Tightness in the labour market is causing this to play out even faster than we anticipated.

In the modern economy, labour is often the most scarce resource; many of us will have heard companies say ‘our most important assets go home at night’. So looking after employees should be one of the key priorities of any business – for both financial and ethical reasons.

How do we assess how well companies are taking care of their employees? As well as looking at company disclosure on things like employee turnover, internal employee surveys and training programmes, we look at employee satisfaction scores and commentary from employee review sites like Glassdoor. Low or deteriorating scores are a red flag to us that suggest staff will leave if they have the economic option.

British bakery chain Greggs is a good example of an employer that manages its employees well. The company doesn’t seem to have been as affected by the labour shortages reported. We put this down to a loyal labour force and the fact they pay a profit–linked bonus to everyone (including students and part-timers) every year.

US retailer Target is another company that, as a result of its employee benefits, including fair wages, is experiencing unusually low turnover in staff despite record-high national quitting rates.

Workers have the bargaining power

The balance of power has shifted to the worker for the first time in decades. Employees are using their newly-found bargaining position to demand more from their employers –they want decent wages, career progression and greater flexibility to come with their job.

We believe human capital is a powerful value creator and as sustainable investors, it’s important to us that the companies we invest in can show us that they are taking care of their people.