China’s President Xi Jinxing himself once called the One Belt, One Road Initiative (OBOR), rooted in the Silk Road spirit of cooperation and connectivity, the ”project of the century“. But can the initiative help drive away the clouds of economic doldrums and channel more positivity towards global economic growth? What are China’s global ambitions in pushing ahead with OBOR? Allianz Global Investors tries to anwer this questions.

Trade – time to explore new markets

With the admission of China to the World Trade Organisation (WTO) in 2001, globalization and favorable demographics facilitated the rise of China as a global manufacturing hub, though China’s aging and shrinking working age population as well as rising trade protectionism have eroded its competitiveness in low-end manufacturing. Thus, China has to move up the value chain while changing its growth model from an investment and export-driven to a more domestic-oriented economy, but also look for new export markets at a time of escalating trade conflict with the US.

On the back of trade tensions, China itself is looking for other alternatives to either move further ahead with its aspiration of being a global leader but also to support its domestic economy. For the first time, this aspiration became clear at the annual meeting of the World Economic Forum in 2017 in Davos when President Xi Jinping said that:

“It is true that economic globalization has created new problems, but this is no justification to write economic globalization off completely. Rather, we should adapt to and guide economic globalization, cushion its negative impact, and deliver its benefits to all countries and all nations”. He moved on to say that “integration into the global economy is a historical trend”.

The One Belt, One Road Initiative

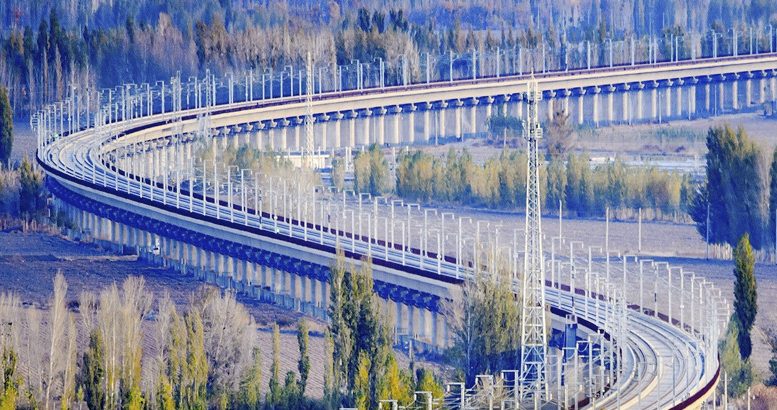

The OBOR initiative, also known as the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), is an attempt to finance and build infrastructure as well as support trade and connectivity among almost 70 mostly developing countries that collectively account for over 30% of global GDP and world trade as well as more than 60% of the world’s population. In general, there are two ways to improve regional cooperation and connectivity: either via the land-based Silk Road Economic Belt (SREB) that overlaps the historical Silk Road, or via the New Maritime Silk Road (MSR). This initiative should economically benefit both China and all other countries participating as their comparative advantages are highly complementary. What is interesting, though, is how the rhetoric has expanded to include a “Silk Road on Ice” or even a “Digital Silk Road”, based on the original idea of the Silk Road connecting East and West.

Where is the funding coming from?

With the initiative, China established the Silk Road Fund in 2014 with an initial USD 40 bn of capital. The fund mainly provides investment and financing support through a variety of forms of investments and loans, primarily equity investments, for trade, economic cooperation and connectivity under the framework of the Belt and Road Initiative.

− In the same year, 22 countries signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) to establish the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) in order to improve economic and social development in Asia by means of sustainable infrastructure, cross-border connectivity and private capital mobilisation (as of July 2018 membership had increased to 87). The subscribed capital stock of AIIB will be USD 100 bn with USD 20 bn as paid-in capital made in five annual instalments.

− At the end of 2016, the China-Central and Eastern Europe Investment Cooperation Fund was set up to invest over USD 50 bn in infrastructure projects and the manufacturing sector in Central and Eastern Europe.

In 2017, during the last Belt and Road Forum in Beijing, President Xi Jinping announced that China will add RMB 780 bn (around USD 110 bn) in funding to the OBOR programme:

- an additional 100 bn RMB (~USD 14 bn) to the Silk Road Fund,

- special-purpose loans to support the infrastructure construction, capacity and financial collaborations (RMB 380bn) provided by two state-owned Chinese banks

- and RMB 300 bn from an overseas RMB fund set up by financial institutions.

However, as big as the numbers sound, they are equivalent to about 1% of China’s GDP and the spending may be spread over a few years. China’s outward direct investment totaled USD 170 bn in 2016 while real money spent in countries in the scope of OBOR was only USD 15 bn according to China’s Ministry of Commerce. However, as of July 2018, total approved projects by AIIB had reached USD 5.3 bn, primarily via sovereign lending, whereas the Silk Road Fund had invested around USD 4 bn since the end of 2014.

Substantial infrastructure shortfall

There is no doubt that the need for infrastructure across Asia ex China is huge: the annual infrastructure investment required to maintain current growth levels in Asia until 2030 is around 4% of GDP for emerging Asia ex-China, based on estimates of the Asian Development Bank (ADB). On closer examination it becomes clear that there is a substantial demand for infrastructure and a shortfall for emerging Asia specifically, which accounts for 61% of developing Asia’s projected 2016–2030 infrastructure investment, whereas China captures the biggest chunk (58%), followed by India (20%).

In terms of sectors, power and transport are the two largest sectors – with climate change factored in – accounting for 56% and 32%, respectively. Overall, AIIB estimates that there is a USD 21 tn financing gap between the region’s demand for infrastructure, projected to be USD 40 tn from 2015 to 2030, and its available financial resources.

However, criticism of OBOR is recently becoming louder:

1) China may gain access to strategically and geopolitically important locations, such as areas in the South China Sea;

2) Many countries are developing a growing dependence on Chinese financing and construction and may find themselves in a situation in which they realize that nothing is without costs.

China is trying to establish itself as one of the biggest aid donors, not only in Africa but also in the Asia-Pacific region, and is mainly channelling money in the form of loans into infrastructure projects such as bridges or highways. However, this comes with certain side effects as China is likely to strengthen its economic and (geo)political ties in order to expand its strategic influence in the region.

Against a background of economic development prospects, the Namibian government, for instance, is unsatisfied with the costs associated with some infrastructure construction projects as they are projected to be higher than initially expected; the government in Malaysia is trying to renegotiate about USD 23 bn of China-backed infrastructure projects due to ”unequal treaties“; Pakistan, Laos, Montenegro, Cambodia, the Maldives and Sri Lanka are showing signs of stress due to a surge in goods imports related to OBOR projects which have led to a trade deficit and could potentially result in a balance of payments crisis.