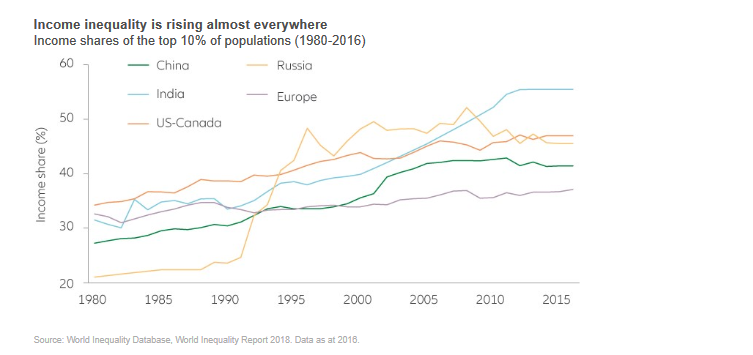

Even though extreme poverty has fallen in recent years, economic inequality has grown more pervasive. In a brief note from the strategist Neil Dwane at Allianz Global Investors, the firm underlines this figure: the top 1% of the US population owned more than 38% of the country’s total wealth in 2016. But as the accompanying charts show, this is not just a US problem: economic inequality is rising worldwide, and the top 10% of populations are benefiting disproportionately.

In addition to having a human cost, it drags down economic growth and destabilises social systems, and it stresses government spending and revenue streams. Yet while there’s no easy fix, there are ways to narrow the inequality gap. Policy makers can focus on social safety nets, taxation structures and educational systems; corporations can boost training, compensation and sustainability efforts; and investors can promote responsible corporate governance. And we must make this a highpriority global effort: inequality is one of the most pressing social and economic issues the world faces today.

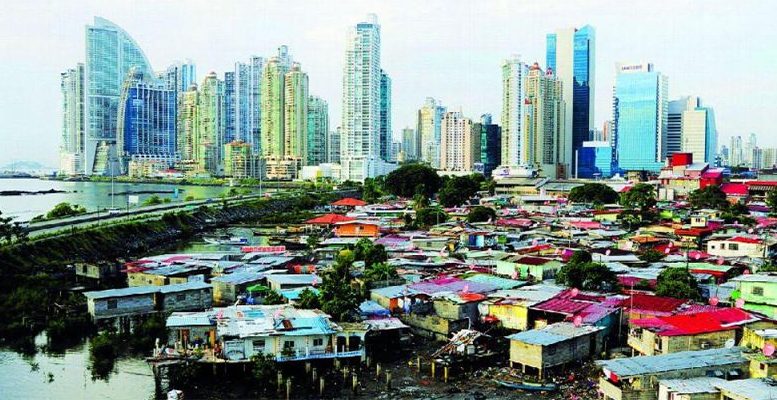

How pervasive is economic inequality? According to Neil Dwane while society has always had its share of haves and have nots, “economic inequality – the uneven distribution of income and wealth – is arguably more widespread now than at any point since the Industrial Revolution.”

Multiple factors are driving inequality higher

In recent years, globalisation has given rise to global manufacturing, enabling goods to be produced in low cost centres and increasing the affordability of consumer products, including hightech goods. But this shift of activities to developing nations has hollowed out industries in developed countries, including traditional big employers such as mining and steel.

The rise of robotics, automation and artificial intelligence will also threaten conventional jobs in the future. Together, these and other developments have reduced the traditional work opportunities that once supported large segments of the population. This has made income and wealth inequality worse and created a growing opportunity gap – particularly for the next generation.

Financial globalisation via the deregulation of financial markets has also played a role in making inequality worse by helping those who have wealth to increase it. In this sense, the strategist from Allianz explains:

Those who were able to invest in the financial markets since the 1980s have done extremely well – particularly in the last 10 years, thanks to central banks’ extremely accommodative monetary policy pushing up asset prices across the board. By contrast, the large number of people who don’t invest in risk assets have found themselves left increasingly farther behind. Enabling more people to participate in the “risk premium” of financial assets is clearly part of the solution.

While economic inequality may be rising, extreme poverty has dropped around the world.

It is fair to say that income inequality as a measurement tool doesn’t always paint a full picture: a struggling nation can suffer from crippling poverty while being low on the income inequality scale.

In most countries, however, governments are paying close attention to economic inequality – just for different reasons: In the emerging world, where most wages are low, wealth inequality is the bigger issue. Not enough people own their own homes or have sufficient savings or pensions. In developed markets, a decreasing number of wealthy individuals shoulder more of the tax burden. Moreover, the social safety net is growing strained as everlarger portions of the population are unable to afford basic living expenses, quality medical care and retirement savings – exacerbated by the rising, inflationary costs of health care.

Worldwide, economic inequality is a destabilising force: it creates distrust and undermines cohesion, increasing the appeal of factional politics. Moreover, in a world of ultimate openness – aided by social media – people today are more aware of what they are “missing” than were previous generations.

Neil Dwane comes to the conclusion that this not only boosts populist politics, but it has a social cost: when people perceive they have fallen behind, they can be more stressed, grow less healthy and make riskier decisions as they try to catch up.