Monetary policy is not equipped to control the real economy and the financial economy at the same time. The aim of monetary policy is to moderate the fluctuations in real variables, GDP, employment and prices. But this destabilises the financial market, fuels speculation and increases household and corporate debt with the banks.

Here are various graphs which demonstrate this.

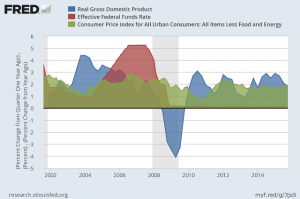

1) In the first one, we can see that things develop with a degree of normality on the front of real variables, or flow variables: GDP and prices. The Fed anticipates a certain amount of inflationary pressure and gradually raises its official interest rates (the red area) from 1% in 2003 to 5.25% in 2006. Greenspan started the increase before he left and Bernanke continued.

However, what happened was that they did not control inflation without huge traumas and they ruined the economy, with GDP falling to 4% in 2008, as can be seen in the blue line. Why? The answer is in the next graph.

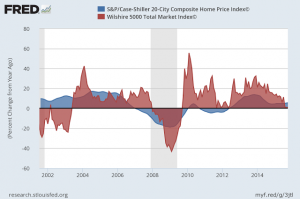

2) While GDP and consumer prices adapted to the new situation, there was a huge catastrophe on the financial front. In the first place, before interest rates were increased, a housing bubble had erupted. This was partly fuelled by the very low rates of 1% and expectations that these were not going to rise for some time, and then only gradually.

But the “gradual” rise in rates meant it became more expensive to maintain positions, which sparked the sale of stock market and property assets. It was impossible to hold on to liabilities covered by assets which were tumbling in price. As we can see, the variations of assets are much more virulent, savage and faster than the variations of those variables which monetary policy wants to control: GDP, employment and prices.

Unfortunately, this virulence affects flow variables and not in a gradual way. As we can see, financial elements have begun to take off again which is not exactly reassuring.

To sum up, the aim of monetary policy is to moderate the fluctuations in real variables, GDP, employment and prices. But this destabilises the financial market, fuels speculation and increases household and corporate debt with the banks. And when the upward cycle ends, people are overdrawn and assets have easily lost half or a third of their price. This is what Irving Fisher called “Debt Deflation” in 1929. Deflation with debt, which is not easy to exit.

Monetary policy can only remain independent from those financial effects which destabilise everything if it once again takes strict control of certain banking activities. The control of cross-border operations is the only way that weaker countries can remain apart from financial turbulence.