By Luis Arroyo, in Madrid | Why did the euro seem to work so splendidly after just a few years …to be about to crash now with such almighty noise? Here I suggest an explanation, which is simple and incomplete and yet, crucial.

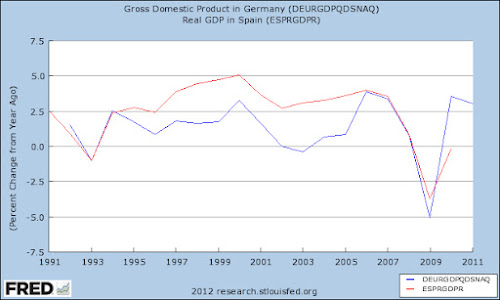

In the first graphic, we see the Spanish real GDP in red and Germany's in blue both at annual growth rates. The drop in the 1990s is remarkable, isn't it? Germany sharply slows down because of its reunification process, an expensive operation with which Germany's buoyant western side re-floated the eastern side's economy. Only a strict discipline could have ensured the success of that feat without social protestation. Germans are proud of their nation and its division was humiliating, and a reminder of an unjust war and the Nazi regime.

In any case, western Germany was extremely generous with its fellow citizens in the east territory and an eastern mark was transformed into a western mark without discount. Digestion of this decision took a long time.

The consequences were a lower economic growth, with low interest rates, as the following chart shows on the blue line. The spread of Spain's bonds was huge, as you can see, but because of devaluation risks instead of default risks. The euro brought both rates together. What happened? The common currency turned around expectations: devaluation risks vanished and the Spanish debt obtained the status of being as safe as Germany's.

click here How to win back your exfull wp-image-10754″ title=”” src=”http://www.thecorner.eu/wp-content/uploads/2012/06/2012-00-52.jpg” alt=”” width=”500″ height=”300″ />

Hence the distortion. While it was reasonable for Germany to bear a low yield, Spain began to enjoy the pleasures of the bubble. At 3 percent interest rates, one could finance mortgages at 40, 50 years, and home prices rose and rose like they were never to come down. We all know the story. The external private debt began to grow, too, like a balloon (Spain's public finances are much, much better, by the way).

For Germany, though, this is good and helps it recover from its internal integration process. Economic cycles, then, diverge instead of converging as we had been promised.

Spain, Ireland and others let themselves go into excesses. Debt financed assets, like houses, suffered a dramatic downturn and all of a sudden they found out that they were poorer, didn't have as many jobs as before, but had to repay their debts, nonetheless. Some States, we must admit, got more into debt not to support the economy but to spend in populism and lies, the same lies that now impede governments to directly inject capital into ailing banks.

Spain needs low interest rates right now, to pay back its debts and strengthen its economy. That is what central banks are for, they should aid troubled banks to stop systemic defaults and sustain the GDP to close debts.

But the contrary has occurred. While in the US interest rates have fallen to historical minimums, in Spain, Italy and Greece they are high in the sky to a point that it's impossible to balance the public finances and default approaches. The euro, as it is, cannot fix this.

1% is “high in the sky”? By historial standards is a very low mark.