Scope Ratings | Since the global financial crisis, the European banking industry has moved in a much safer direction, with new regulations triggering a profound re-think of business models and risk/return combinations.

The Capital Requirements Regulation and Directive, the Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive and their subsequent updates have led to significant reductions in leverage, while more proactive supervision has led to the de-risking of legacy bad assets.

For their part, a new breed of bank managers has steered business models away from risky and capital-intensive activities to lower profitability businesses and shed the aggressive cash-financed acquisition model.

Since the creation of the European Banking Union, credible regulatory stress tests have validated the narrative of a safer, more stable European banking industry. Stress-test failures have been few and far between in recent years and limited to marginal players whose balance sheets were irreparably damaged by the previous credit cycle.

But the proof of the pudding is in the eating, and the Covid crisis is the banking sector’s first real-life stress test since the GFC. Despite deep damage to the economy, we see no signs yet of a banking crisis. This is partly the result of the significant fiscal policyresponse that has included direct public-sector support to households and companies in the form of grants, generous furloughs, and tax breaks. It is also due to the material relaxation of accounting and solvency requirements which has provided banks and their clients with breathing room.

In addition, the strong financial fundamentals of banks entering the crisis, played a paramount role in avoiding a credit crunch that would otherwise have exacerbated the initial output shock of the lockdowns.

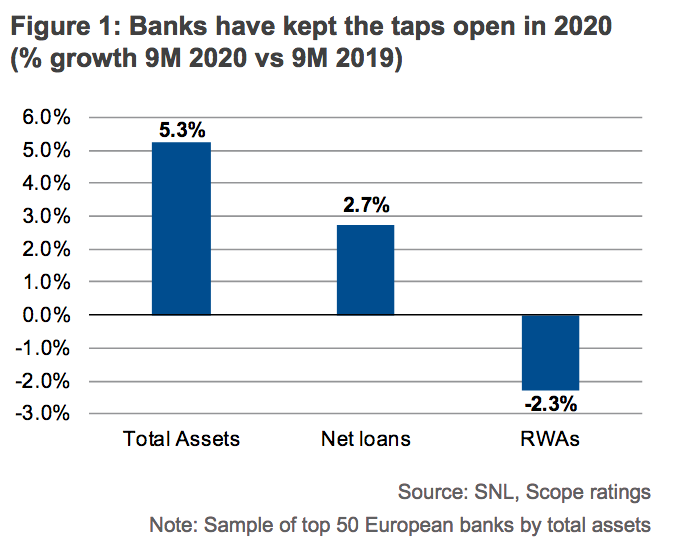

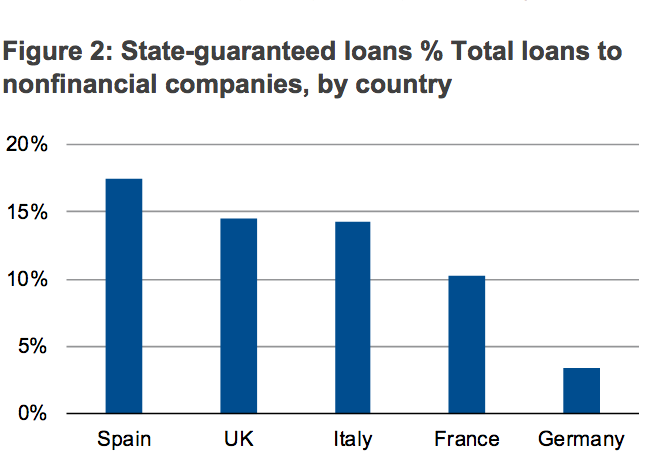

At the end of September 2020, European banks’ balance sheets were 4.4% larger than a year before, bloated by TLTRO liquidity and central bank asset purchases. Loan growth was there too, though RWAs were down at most lenders. This was in large part due to the lower risk-weight of lending under public guarantee schemes. We note, however, that they are not all fully guaranteed and will not fully benefit from public backstops if asset quality deteriorates.

According to the EBA’s stocktake on moratoriums and public guarantees published in November 2020, EU banks had EUR 162bn in exposures under public guarantees as of June 2020, with the corresponding RWA figure being only EUR 29bn. The implied average risk-weight of 18% is one third of the average risk-weight for non-financial corporations not under public guarantee schemes (54%).

But we are not out of the tunnel yet. Achieving herd immunity through vaccinations is still several months away, and there remain several question marks over the strength of the economic rebound and the depth of the credit cycle. Public support measures are expected to taper in 2021, leading to a belated increase in non-performing loans. The path of fiscal consolidation and monetary normalisation is highly uncertain. The only certainty is the increased size of the public-debt stock and central-bank balance sheets along with a re-engagement of the sovereign-bank nexus in highly-indebted euro area economies. Authorities will have to walk a tightrope, with limited room for mistakes.

Our baseline scenario reflects the second round of lockdowns in Europe followed by a bumpy recovery in 2021. On this basis, we expects the euro area economy to recover by 5.6% in 2021, after a severe 8.9% contraction in 2020.

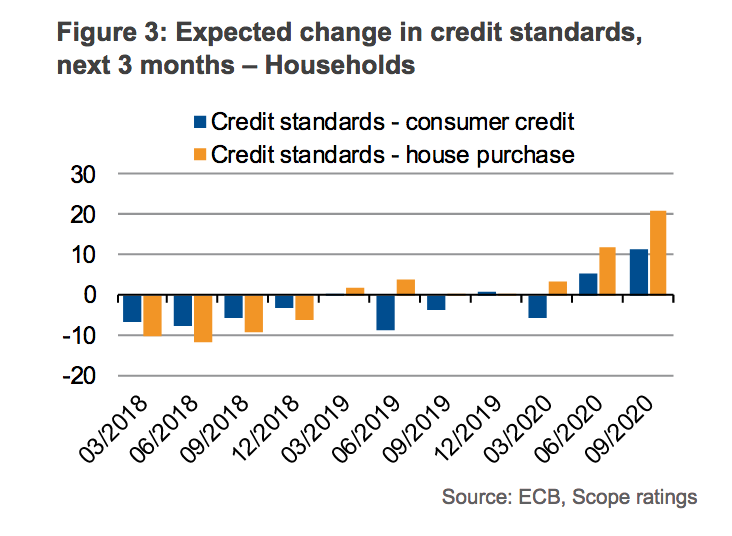

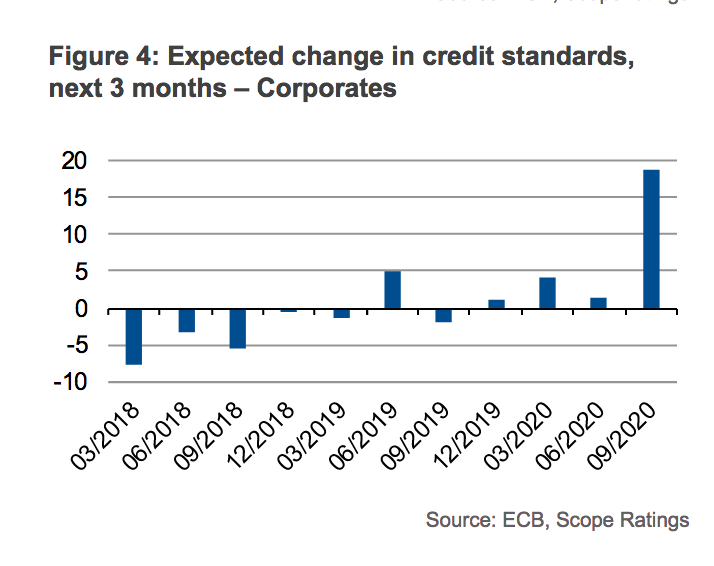

How banks navigate the Covid recession and its aftermath will shed light on whether the new regulations were successful in ensuring that the sector has turned from a source of financial instability into a stabilising factor at a time of high macroeconomic volatility. One key area to monitor is the extent to which banks will continue to support the economy throughout the late phases of the pandemic and through the rebound. Worryingly, the latest ECB lending survey data points to tightening credit standards in the euro area.