Is the crisis over or not? Should we be optimistic or better yet cautious about the development of the economies of central Europe? The economists, politicians and entrepreneurs meeting up at the annual economic forum in the southern Czech town of Krynici in the first week of September were unable to come up with a definite answer, even when politicians, with Polish Prime Minister Donald Tusk in the lead, tried to put the most upbeat spin on it.

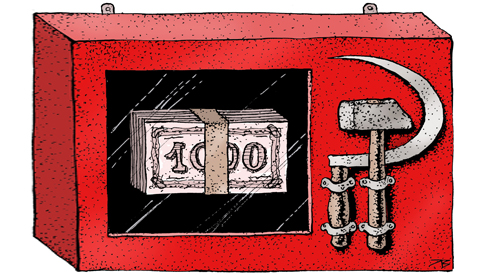

What came to the surface once again, and strikingly so, perhaps more than ever before, is just how far the economies of central Europe still hang on the decisions, whims and mindsets of politicians. After more than 20 years of building free-market capitalism one would expect that a business would act independently of politicians, and on the other hand, that politicians would not indulge themselves in notions such as those of Jaroslaw Kaczynski, who announced from the podium to dozens of entrepreneurs that if his party wins the election it will raise taxes. On top of that, Kaczynski argues, Poland needs a stronger state.

Polish paradoxes

The relationship between the state and business in Poland is rather a paradox. The bruising reforms of the early 1990s have created a significantly more competitive market environment than Czechs had grown used to during the Klaus era of “bank socialism”. The Polish state, in contrast, has until today retained a strong influence in hundreds of companies.

Although many of them float shares on the Warsaw Stock Exchange, the controlling stake is held by the government. That situation creates hundreds of interesting combinations of influence and the flow of money, which the Czechs know in principle only in the case of the energy company CEZ.

Dozens of such enterprises exist in Poland and the hand of government in them is affecting the economic environment. In particular, it keeps employment high (in mines and armament factories) or takes money from the company books according to the needs of the state budget – as this year, when the insurance company PZU and at least two other companies will apparently pay out advances from this year’s dividends before year’s end.

The Czech liberal environment has been left wonder-struck by the notion of Milos Zeman to spur economic recovery through state investment projects [primarily the Pharanoic plan for a Danube-Oder-Elbe canal]. Czech economists, it would appear, have weaned themselves from pondering the strong role of the state in the economy, while in Poland, Slovakia and previously liberal Hungary, governments are still the main players in it.

*Read the whole article here.

Be the first to comment on "Nostalgia for strong leadership"