James Alexander via Historinhas | The Bank of England published its quarterly Inflation Report for November 2015 last week. The fact that the BoE is missing its 2% inflation target by more than 1% set in train the usual mini-flurry of letters to and from their political masters at the UK finance ministry, aka The Treasury. While reading the Treasury reply I spotted that there had been an “evolution in UK monetary policy”, I was forced to read on.

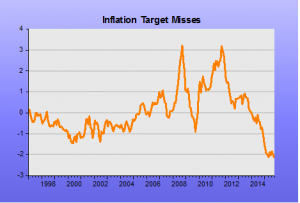

In fact the gap to the 2% target was back to the largest for some time at a negative 2.12% thanks to the most recent CPI itself coming in at a negative 0.12%. Of course, sophisticates prefer one of the numerous measures of “core” CPI, excluding food and/or energy, and/or housing, etc.

Market Monetarists prefer to pay no attention to CPI since it is not a proper macroeconomic statistic, but a political one, since it is never revised. All proper economic statistics have to go through numerous revision processes over time – that is what makes them robust measures of the actual economy. No reliable macro number can be perfect first time. Only faith-based economists look for certainty.

But the Treasury and the BoE are, by statute, stuck with headline CPI as their official target, and the BoE has to explain why it is missing this target by such a wide margin. The correspondence is often quite revealing about what the BoE or the politicians are actually thinking or targeting and the fallacies on which these thoughts are based. All the usual ones were trotted out:

Fallacy 1: The long and variable lags

From the BoE Governor letter to the Treasury

The peak effect of monetary policy on inflation is generally estimated to occur with a lag of between 18 and 24 months.

There is little recent evidence of 18-24 month lags. US monetary policy immediately crashed the world economy in 2008 after the Lehman bankruptcy. The Bank of England was busy doing the same in 2007 and 2008 with its extremely grudging, and therefore massively confidence-sapping and counter-productive, response to a run on its banks. The ECB immediately crashed the Euro Area in mid-2011 when it raised rates twice.

Monetary policy has supposedly been “highly accommodative” as Janet Yellen constantly reminds us, for nearly seven years. It is actually quite destructive of central bank credibility this refrain, and gets repeated by so many really quite smart people. But this supposedly “ultra loose” monetary policy has only engendered the slowest recovery in the post-war years, showing that: a) it hasn’t been very accommodative and b) that the supposed 18-24 month lag are faith rather than being evidence-based.

Fallacy 2: The “spare capacity” theory of monetary policy

From the BoE Governor letter to the Treasury

The MPC judges it appropriate to set policy in order to ensure that growth is sufficient to absorb the remaining spare capacity to return inflation to the target in a sustainable manner in around two years and to keep it there in the absence of further shocks.

We have already commented on central bankers really targeting the two-year out inflation that their macro models generate, and that these models are based on the false Philips Curve theory: that inflation and unemployment are inversely correlated. These central bankers need to look at the track record of both the Great Moderation and the last seven years, abandon the theory as false, and move back to orthodox monetary economics (that monetary policy determines nominal growth), or better Market Monetarism (that expectations of nominal growth are the monetary policy and thus drive actual nominal growth).

Fallacy 3: Consistently missing the 2% inflation target (on the upside) would court disaster

In line with the requirements in the MPC remit, your letter provides a clear assessment of considerations and trade-offs guiding decisions from the MPC when considering the appropriate approach to, and horizon for, bringing inflation back to target, including implications for output volatility and risks of possible financial imbalances. The Government’s commitment to the current regime of flexible inflation targeting, with an operational target of 2% CPI inflation, remains absolute.

Trying to ignore the humour in an absolute commitment to a flexible policy, there is nothing special about 2%. The figure was plucked out of the air one day by central bankers as an ad hoc number around which to organise their weapons to fight much higher inflation. It worked for a while in bringing down inflation from those higher levels, and helped create the space for the Great Moderation. But Inflation Targeting’s time has come to an end as it has become a ceiling and started to interfere with optimal monetary policy. Monetary policy should be set to secure stable nominal income growth along a trend level, not “inflation”. There would be no disaster if we all just stopped talking about “inflation”.

To be fair the Treasury did try to make clear in their letter that the “target is symmetric: deviations below the target are treated the same way as deviations above the target.” I find that a bit hard to believe given the hand-wringing in the commentariat when CPI is above target is only matched by much the same hand-wringing when it is below target but could soon rise above target – according to the false theory in Fallacy 2.

That “evolution”: what is it about 2%?

From the BoE Governor letter to the Treasury

As described in the Inflation Report published today, the MPC’s preference is to use Bank Rate as the active marginal instrument for monetary policy, and expects to maintain the stock of purchased assets at £375 billion until Bank Rate has reached a level from which it can be cut materially. The MPC currently judges that such a level of Bank Rate is around 2%. This is a further evolution of the Committee’s forward guidance framework, which included guidance on the APF, originally announced in August 2013.

We now seem to have two 2%’s in the UK. The flexible inflation target and now some sort of natural 2% rate of interest at which the BoE can “materially” unwind its Asset Purchase Facility (“QE”) and do more than just not reinvesting proceeds from maturing bonds but sell them off too.

Is this really what they talk about at the Monetary Policy Committee? A sort of Fantasy Football League chat about what the future level of interest rates might possibly mean for the economy. Sure, if nominal growth is robust at over 5% and “inflation” bobbing along regularly above 2% then rates might be higher. But why set yourselves up as hostages to fortune and declare that a 2% Bank Rate is the right level to aggressively unwind QE? And why do both the BoE and the Treasury declare this an “evolution” of monetary policy guidance. At the end of the day the rate setters have to talk about something and Fantasy Football League is fairly harmless, I suppose.