The combination of poor profitability and potentially worsening asset quality has pushed to the fore the need for banks to achieve greater operating efficiencies and lower cost bases. The case for cross-border mergers is weaker as the cost synergies are less obvious. This puts the focus sharply on in-country consolidation.

National champions and mid-tier banks will need to scrutinise opportunities to strengthen their market positions in their home countries to generate cost savings.

The Caixabank merger envisages cost synergies of 42% of Bankia’s cost base, for example.

M&A can help accelerate branch closures and associated efficiency gains. Clearly, mergers create branch overlaps, allowing banks to consolidate the customers of two branches into one. But the benefits of greater scale will also be seen in bigger budgets to drive critical digitisation efforts in the wake of evolving customer needs.

The consolidation narrative has already led to the beginnings of a media frenzy around European bank M&A, including reports of merger talks between UBS and Credit Suisse.

A lot of attention will fall on Spain and Italy. Banking markets in both countries continue to be fragmented, with several mid-scale banks that as a group have become subject to consolidation talk,either as mergers of equals or as add-ons to national champions(such as the case of IntesaSanpaolo/UBI Banca).

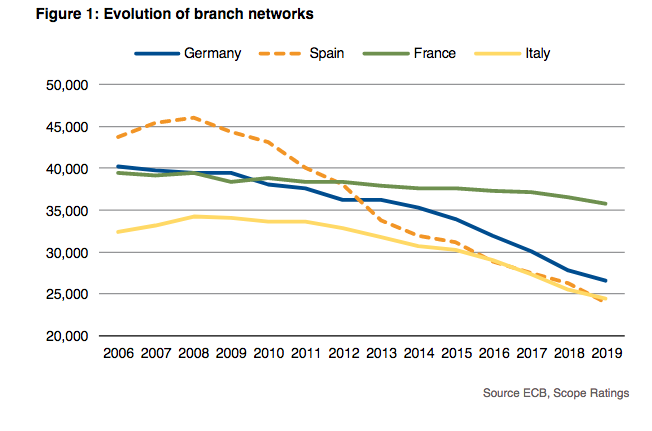

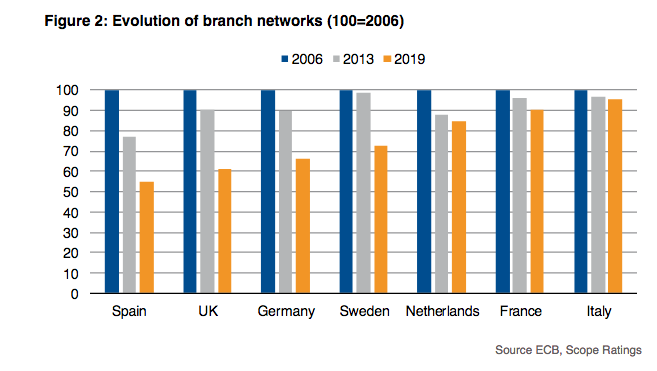

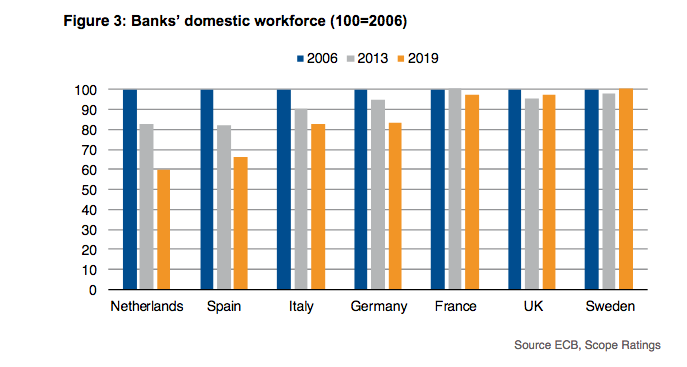

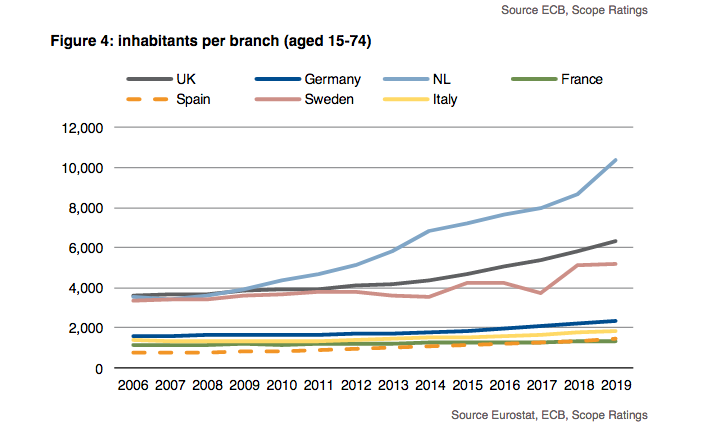

Spanish banks have made drastic efforts since the global financial crisis to improve efficiency. They were among the most active in Europe to adjust their branch networks (see Figures 1 and 2). But while the number of branches has reduced in many countries, the workforce has not always followed the same pace of adjustment (Figure 3). There is still room for efficiency gains, particularly as digitisation continues.Taking into account the respective size of populations in several European countries, efforts by Spanish banks have been no more than playing catch-up and done no more than kept them on a par with peers in other countries like France, Italy or Germany (Figure4). Transition in Spain can only accelerate, leaving room for consolidation.

After the global financial crisis, Spain’s “proximity banking” model took a serious hit as large branch networks had primarily been explained by the need to gather scarce deposits when competition was high and the availability of cheap funding was a real constraint. The deleveraging that followed Spain’s real-estate crisis over the past 10 years translated in a lower overall need for funding; even more so as central bank money started to become available to banks reliably and in size.

At the same time, the decline of interest rates has reduced the attractiveness of holding excess retail deposits. These are now seen as an expensive luxury as they need to be parked with the central bank at a negative rate and banks have stopped short of passing on negative rates to retail customers.

More seminal changes to banks’ operating models are being brought to bear by rapidly changing customer behaviour. Customers are actively embracing new technologies, which questions the value of large branch networks. Covid-19 has accelerated this process, and banks now have an imperative to further reduce their networks. This process is not a sprint but a marathon. The finish line may ultimately be the disappearance of bank branches from the high street in scale.

In some countries in Northern Europe, such as the Netherlands, a single branch can serve up to 10,000 customers. That is approximately seven times the number of customers served on average by a bank branch in Spain. The process, even in these countries –which are a lot more advanced in the shift to the new normal –is ongoing. Sweden’s Handelsbanken, for example, recently announced it is almost halving its branch network from 380 to 200 by the end of 2021 as digitalisation among its customers has progressedto such an extent. Deutsche Bank, meanwhile, is reported to be contemplating cutting 20% of its branches in Germany