This article was originally published on Fair Observer.

The forced devaluation of Argentina’s official exchange rate, restrictions on the currency exchange market, inflation, and flaws in transport and infrastructure are the worst sides of an economic model that has prioritized consumption over sustainable growth. International indexes reflect that since 2003, the Kirchners’ economic policies have been based on high levels of public expenditure, subsidies and soaring levels of consumption, which have helped the country’s gross domestic product (GDP) increase at a surprising rate.

However, politicians and economists knew this model would not last forever. By maintaining a high growth rate and high levels of consumption, much needed changes that should have accompanied Argentina’s progress were put off. Plans to upgrade the country’s infrastructure, as well as adopting incentives on private investment and programs for a better exploitation of Argentina’s natural resources were shelved. In 2006, Néstor Kirchner’s former economic minister had warned:

“There’s a big risk [in decisions that the presidential office has to make], that is to accumulate mistakes that won’t be noticed in the short-term … I don’t know which is the course of politics, but I can notice a temptation to give easy subsidies or to assume from the public sector investments that could be done by the private sector.”

From 2008, the ruling party has covered its deficiencies with a set of unorthodox measures that have aimed to keep economic variables balanced, but at the same time undermine the government’s credibility. The Argentine government has altered its official statistic indexes; forced price agreements with the private sector; created restrictions on imports and the currency exchange market; expropriated an oil company, Yacimientos Petrolíferos Fiscales; and implemented diverse measures in order to maintain good levels of consumption and growth.

But a very high international soybean price and the discovery of new energy resources in the province of Neuquén (Vaca Muerta) encouraged the government to incorrectly assume that adjustments were not needed. Until 2013, rises in salaries exceeded inflation rates, even by the private sector’s standards. The Kirchners’ economic model remained successful, although it was increasingly convoluted and complex. However, none of these solutions resolved the real problem.

Following the re-election of President Fernandez in 2011, cracks began to surface: a widening deficit; the failure of local industries to meet demand; deficient and outdated infrastructure; and a lack of investment in the labor market. Over time, Argentina’s growth was simply not enough to sustain the country’s demands. In fact, since 2010, Argentina has spent millions of dollars from its central bank reserves on trying to import energy, as big cities and industries have suffered power outages. Moreover, on February 22, 2012, a tragic accident in one of Buenos Aires’ train stations left 52 people dead. Evidence later showed the train had an outdated braking system, while the station had poorly constructed barriers that failed to stop the incoming train. A lack of investment and high levels of corruption are still being investigated by local authorities.

Even worse, economists often agree that growth generates certain levels of inflation. This phenomenon is natural and controlled when growth is sustainable and part of a solid economic strategy. But when growth is based only on consumption, high inflation ends up being a very bad symptom for a country. According to calculations by Argentine opposition parties, inflation in 2013 stood at 28%, one of the highest in the world. For the current year, union representatives have already declared they will not accept less than a 30% increase in salaries.

During the first quarter of 2014, the government decided to devaluate its currency and remove some controls it had introduced to ban Argentines from exchanging pesos into dollars. Furthermore, efforts are being made to obtain international credit but first, Argentina must strike a deal with its existing creditors. Recently, an agreement was signed with the Paris Club in expectation that this will pave the way for new loans.

An Out of Touch President?

Another landmark in terms of international debt and access to credit will be the decision that the US Supreme Court has to make in a case between the government and a fund that holds Argentine debt. Argentina has already stated that losing the case could force a new default. On the other hand, if the country manages to win that case, the situation could change significantly.

However, hopes for the region and the country will be high, if Argentina manages to fix its economy with a solid plan. The current economic situation was self-generated by an irresponsible policy that needs to be corrected by the Fernandez government. A key task will be to regain credibility in the eyes of the international community, private investors and among its own population. In failing to do so, no economic plan will be able to save Argentina from a new economic crisis that could have a catastrophic impact on the nation. The most difficult thing for the government will be to retrace all of its bad decisions and rebuild confidence.

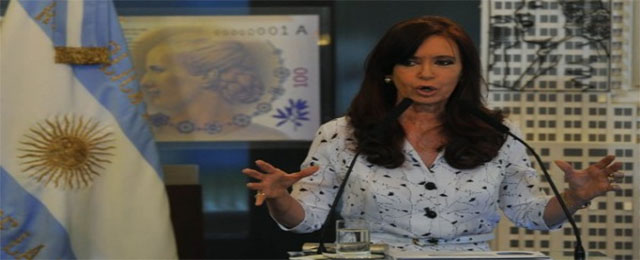

The outlook does not look good with a president that has decided to take a back seat. Argentines are beginning to think that Fernandez is out of touch and has no strategy in place whatsoever. National elections will be held next year and the president could very well suffer a loss at the polls. The result will be determined by the way Fernandez’s administration handles the economic crisis.

This article was originally published on Fair Observer.

Be the first to comment on "Argentina and the economic crisis cliff"