An unwritten rule seems to warrant that US defence spending is kept immune to the ups and downs of the nation's GDP. The extraordinary dimensions of the current economic downturn, nevertheless, is testing its past resilience to any sort of moderation.

Public investment in military affairs has largely been the result of foreign policy and global strategy, government cabinets since 2001 would surely protest from Washington. But a federal deficit larger than the euro zone's average, and growing, comes into the picture when describing latest developments in this section of the budget. Analysts at ratings agencies talk of the real possibility of one or more major programmes being finally eliminated altogether, and small defence contractors suffering the most because they lack flexibility and have little diversification.

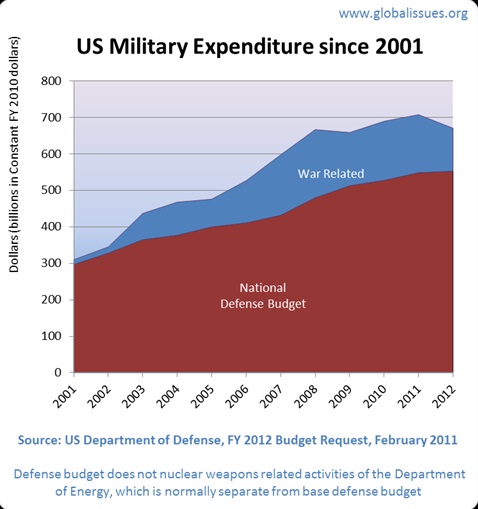

The wind-down of the US presence and action in Afghanistan is but a fractional aspect of the overall cutbacks. There is the Budget Control Act of 2011, which initially imposes $487-billion defence spending reductions by 2021 and could slash public investment by up to $1 trillion if automatic, across-the-board contractions were to be put in place from January next year, as scheduled.

And there is the base 2013 defence budget, which will be $6 billion inferior to the 2012's and $45 billion under the figure set by the Department of Defence. Comparing to Obama administration's own forecast numbers, spending during the next five years will be

clipped by 9 percent. The Pentagon also seeks savings by 2017 of $50 billion, with aircraft purchases decreasing by $6 billion next year (179 fewer F-35s and 24 fewer V-22 tilt-rotors, plus a C-27J cargo aircraft and one Global Hawk high-altitude unmanned aerial vehicle in the process of being cancelled).

Understandably, the US interventions in Iraq and Afghanistan had bloated defence spending needs. But already last year president Obama and secretary of Defence Leon Panetta signalled it was time to turn the page. The focus of US foreign military policy is shifting from the Middle East to Asia, and the new goals involve some homework, too: less personnel, less maintenance and compensations costs, less equipment.

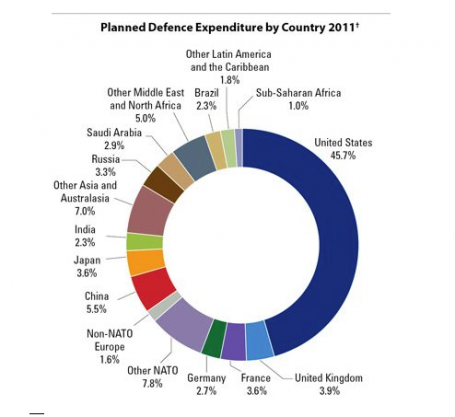

The debate about the extent to which these moves in defence spending respond to the urgency of reigning in the deficit belongs to politics. Regarding the defence industry, analysts expect that US companies will be able to edge a decline in domestic demand by increasing sales in the Middle East and Asia, even if it will not offset full losses. Some European firms will feel the pain, too, because of their links to the US market, like UK's BAE Systems or Italy's Finmeccanica SpA.

But a US foreign policy with less steel and more diplomatic muscle sounds like good news.