BoAML | Despite the volatility in capital markets, the global economy remains on track for another year of modestly below-trend 3% growth. In June, our GLOBALcycle coincident indicator showed improvement for the fifth-straight month, reaching index levels not seen since the summer of 2014.

It´s alright

Business conditions improved notably in emerging markets (GEM) but pulled back slightly on net in developed markets. In the US, initially very weak GDP data for 4Q and 1Q has been successively revised higher. Data for the second quarter have improved. Payrolls weakened sharply in May, but bounced back in June, jumping 287,000. Capital goods orders remain weak, but retail sales have picked up and purchasing manager surveys have improved. Overall, 2Q GDP is now tracking 2.6%. We remain comfortable with our call for roughly 2% growth.

Voting the island off

After Brexit, we followed through on our scenario analysis, penciling in a full-blown UK recession, cutting 0.5% off of Euro Area growth and slicing 0.2% off of US and global growth. Events since Brexit have not changed our call. The pound has plunged more than 11% since the vote, and both consumer and business confidence have tumbled. However, the spillover outside the UK is contained thus far. The USD/Euro remains near the middle of its 1.05 to1.15 “trading range” of the last year and a half. Brexit has put pressure on European already vulnerable bank stocks, but it has not caused further “fragmentation” in Europe—spreads between bond yields in the core and periphery of Europe have been relatively stable. Global equity markets initially sold off sharply, but have recovered most of those losses. Bond yields have fallen sharply across the world and overall financial conditions are relatively stable.

Exit aftershocks

The calm response is encouraging. The good news is that referendums in other countries are unlikely any time soon. UK Prime Minister Cameron has shown what a mistake that can be and popular support for fragmentation should ease as the cost of Brexit becomes clear. The combination of a big drop in bond yields and a quick recovery in equities suggests that markets still believe central banks have some ammunition. Nonetheless, we expect some moderate aftershocks in the months ahead. Some of the calm reflects misguided hopes that the decision will either be reversed or Europe will capitulate and offer a sweetheart deal. Comments from politicians in the UK and the rest of the EU confirm that both of these scenarios are very unlikely. In our view, another bit of wishful thinking is that the short-run shock to UK growth will likely be small.

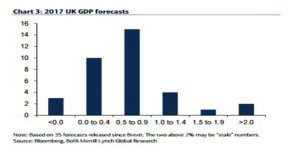

Chart 3 shows the range of 2017 GDP forecasts that have been updated since the shock. We are below the consensus, forecasting a recession with just 0.2% growth in 2017, compared to a median forecast of 0.5%.There is alsoa long tail of more optimistic projections. While there is considerable uncertainty about the exact outcome, we expect the optimistic tail to disappear as reality sets in. Why the optimism? Some economists seem to be discounting the uncertainty shock. As Paul Krugman puts it: “I believe that Brexit … will do substantial long-run economic harm. But what we’re hearing overwhelmingly from economists is the claim that it will also have severe short-run adverse impacts.”

However, “that claim seems dubious” it “doesn’t follow in any clear way from standard macroeconomics – but it’s being presented as if it does. And I worry that what we’re seeing is a case of motivated reasoning, which could end up damaging economists’ credibility.” Krugman continues “Brexit certainly does increase uncertainty – but is this necessarily bad for investment? That’s not at all clear from the theoretical literature: firms might actually invest more in the face of uncertainty, in effect to cover their bases.” Moreover, “any major policy change creates uncertainty, because nobody knows how it will work out. So why don’t we hear recession warnings when countries are contemplating major trade liberalization, or privatization schemes, or labor market reforms?” In sum, forecasts of a recession are based on faulty, biased analysis. The problem with Krugman’s argument is that both theory and evidence point to a very big uncertainty shock, with all risks to the downside.

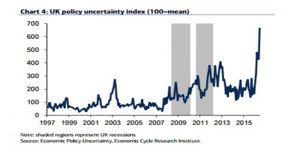

As Chart 4 shows, the threat and actuality of Brexit caused the economic policy uncertainty index for the UK to skyrocket in June. As we argued above, since Brexit both consumer and business confidence have tumbled. Moreover, there are two “standard macroeconomic” arguments for a sharp slowdown or recession. First, there is an option value in waiting to see how bad the outcome is.

Why invest now when you can always invest after you find out whether your sales are down a lot? Second, the accelerator effect argues if the future level of GDP is going to be, say, 2 or 3% lower due to damaged trade, then the capital stock needs to be 2 or 3% lower. Back of the envelope estimates from Rob Wood show that cutting the capital stock by 3% requires 10% lower investment over a 3 or 4 year period.

Brexit, animal spirits and policy ammunition

Outside of Europe, Brexit is best viewed as yet another in a long sequence of confidence shocks. Many of these shocks are due to political dysfunction. The US had a trifecta of brinkmanship moments with the threatened debt default, the fiscal cliff and the federal government shutdown. In Europe, Brexit follows multiple crises around Greece. Japan has suffered a natural disaster and a self-inflicted wound—the recessionary consumption tax hike of 2014. China is going through a difficult restructuring, but also made policy mistakes that destabilized the equity and currency markets. Sharp movements in oil prices and exchange rates have added to uncertainty. The Arab Spring, the refugee crisis and terrorism could be added to the list. These shocks have three longer-run legacies. First, they have dampened animal spirits, causing a seemingly permanent sub-normal recovery in capex and other durable goods spending. Second, they have forced central banks to burn through a dwindling supply of policy ammunition, leaving them vulnerable to a recessionary shock. Third, many of these shocks are self-inflicted wounds, reminding us how populist policy can hurt nearterm growth. Tearing up free trade agreements causes an uncertainty shock in the short-run and an efficiency shock in the long-run. And yet, both US presidential candidates to varying degrees are talking about following in the UK’s footsteps. Our greatest concern in the next few months is an uncertainty shock coming out of the US election. As we noted here, this unusually contentious election could undercut confidence in three ways: (1) both candidates have very high unfavorablity ratings and are working hard to portray the other as unfit for office, (2) the candidates have unusually wide disagreements on a number of issues, creating uncertainty about who will be the winners and losers from new policies, and (3) there are some very aggressive proposals that could hurt growth in the near-term. We don’t think the election is having a material impact on confidence now, but could become important after the July conventions as positions are sharpened and voters start taking a more serious look at the choices. We are particularly focused on corporate confidence.

Thus in the run-up to the fiscal cliff in 2012, we kept a close eye on commentary from corporate leaders, such as the US Chamber of Commerce. At the time their website featured a “countdown to the fiscal cliff.” This was intended to encourage business leaders to lobby for a resolution of the cliff, but we also felt it had the unintended impact of discouraging corporate commitments. Today their website is peppered with articles about the benefits of free trade, the recessionary impact of tariffs and the negative impact of regulations on growth.

Coordinated policy? Don’t hold your breath

After Brexit, a hot story in the markets was that globally coordinated policy action could be in the works and might be needed to stem the risk-off trade in global capital markets. In a limited sense, the major central banks are already “coordinated.” Liquidity facilities are still in place, central banks have become more aware of adverse feedback loops and they seem to be consulting more. Fiscal policy also seems to be swinging from austerity to modest easing in a number of countries, although this is more by accident than design. However, we are a long way from the kind of explicit coordination that some analysts and investors are looking for. Only a major market or economic meltdown would trigger any of the following: • Coordinated monetary easing: This is very unlikely given the very different growth and inflation picture across the world. Instead, we are very likely to see aggressive easing by the BOE, mild further easing by the ECB, BOJ and PBOC and a very slow tightening by the Fed.

- Coordinated efforts to stabilize UK markets: Policy makers, particularly on the continent, do not want to offer blood transfusions for self-inflicted wounds.

- Coordinated efforts to stop yen strength. Again, the necessary alignment of incentives simply does not exist. Only recently Japan was added to the US Treasury’s currency watch list and the US Presidential election has featured strong attacks on “currency manipulation” by both candidates.4 If Japan intervenes, they will likely have to go alone.

- Coordinated fiscal easing: Easing in the US and Europe recently is more by accident than design. Japan keeps flirting with further austerity. In all three regions, internal political battles are driving fiscal policy, making global coordination very unlikely.Two final thoughts. First, despite a variety of risk-off events there has not been a coordinated policy intervention since the Great Recession. It is puzzling why modest risk-off events keep conjuring up talk of coordination. Second, coordination is the opposite of “currency wars.” The currency war thesis assumes that a weaker currency is the only effective monetary policy channel; if correct, coordinated easing is a waste of time. By contrast, policy coordination relies on all the other policy channels—interest rates, bank lending, asset prices, and perhaps most important, confidence. It is hard to imagine that policy makers have done a 180-degree turn in their view of how monetary policy works. A more consistent story is that policy works through all of the channels and if everyone eases, everyone is better off.

*Image: Flickr