Azad Zangana (Schroders) | November 2020 was the fourth consecutive month that headline inflation for the eurozone – using the harmonised index of consumer prices (HICP) – was negative. The response to the coronavirus pandemic has caused the most severe economic shock across the continent since the Second World War.

Even after the summer rebound in growth, compared to the end of last year most member states are showing shortfalls in GDP that are greater than the depths of the global financial crisis. This has raised fears of the return of deflation which at present poses a more significant danger than in 2009 or 2015, as monetary policy appears close to the limits of its efficacy.

With movement restrictions being reintroduced to quell a resurgence in infections, the economy is expected to dip again in the final quarter of this year, and potentially at the start of 2021. This will add to the excess spare capacity across the monetary union, raising deflationary pressures.

Here we consider the extent of the risk of a return to deflation, and the likely implications for monetary policy in 2021 and beyond.

Worrying trends

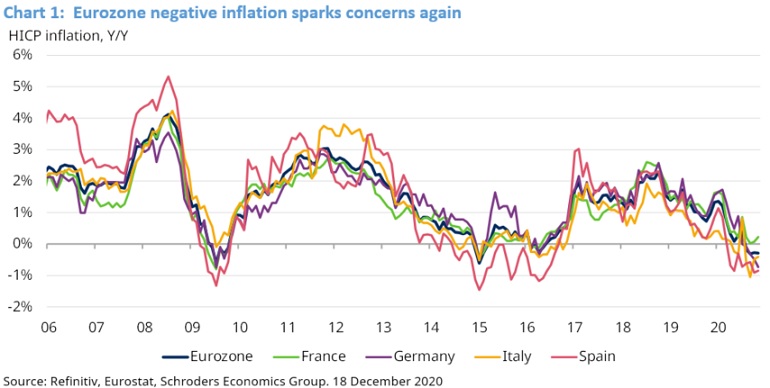

The concern among investors stems from the low rates of inflation seen over the past decade, along with two notable periods of falling prices. The disinflation bout of 2009 was relatively short lived, but the period following the sovereign debt crisis was more severe. With interest rates close to zero the European Central Bank (ECB) began asset purchases, or quantitative easing, for the first time. Yet the period of concern lasted around three years for the monetary union (see chart 1).

oday, inflation in Germany, Spain and Italy is in negative territory, with France just above zero. The fear is that with interest rates already below zero, the ability of the ECB to raise inflation appears very limited. This is especially true given that EU treaties outlaw monetary financing, often referred to as Modern Monetary Theory. To make matters worse, several indicators point to mounting deflationary pressures, which should be noted.

Deflation vulnerability index

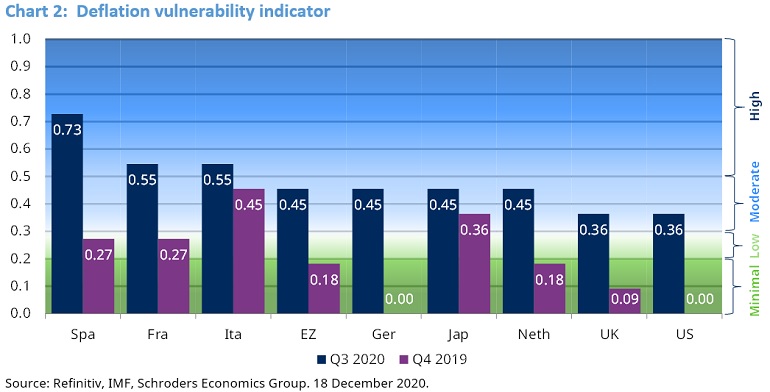

To better assess the eurozone’s risk of future outright deflation, we have once again updated some analysis from the International Monetary Fund (IMF). The research attempts to measure and flag the risk of deflation with a two-year outlook.

The deflation vulnerability indicator is a simple composite indicator that summarises whether a critical number of macro variables have reached a level that would warrant concern. These indicators include inflation itself, measures of spare capacity, equity market performance, along with lending behaviour and real effectivenexchange rates.

There are 11 criteria. If all aretriggered, they give a maximum score of one. If more than half are triggered, then the model deems there to be a high risk of deflation in the subsequent two years. A score of between 0.3 and 0.5 suggests moderate risk; 0.2 to 0.3 suggests low risk, and finally, zero to 0.2 suggests minimal risk. For more on the methodology of the deflation vulnerability indicator and to revisit our previous analysis, see the March 2014 Economics & Strategy Viewpoint.

At the end of 2019, the eurozone aggregate score was signalling minimal risk of deflation, though Italy was flashing moderate risk. Spain and France were showing low risk. The latest signal for the third quarter of 2020 suggests the risk of deflation has risen to a moderate level for the eurozone, but is also high for Italy, France and Spain (chart 2).

For comparison purposes, Japan’s risk of deflation has remained at moderate levels, while the risk for the UK and US, have also risen from minimal to moderate.

Given that inflation is already negative for the eurozone aggregate, the above analysis is really flagging the risk of a prolonged period of deflation. The deflation vulnerability indicator did a good job predicting the phenomenon back in 2014, and so should be heeded. However, there are other factors that need to be considered which suggest that this period of disinflation may be short lived.

Tax distortions

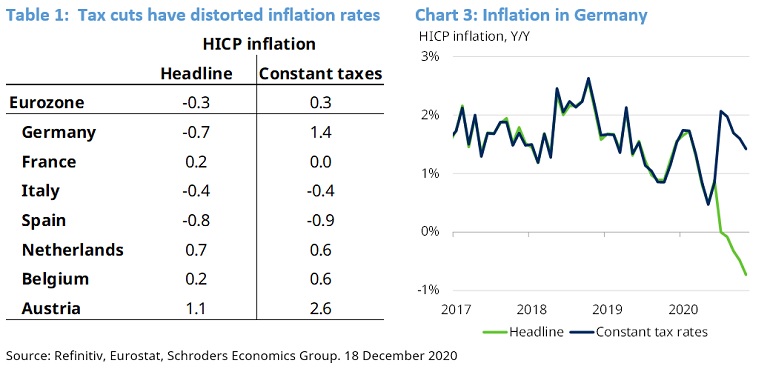

Headline inflation is often impacted by tax policy. Of course, austerity tends to lower demand and price pressures, while fiscal stimulus can boost demand and push prices higher. In this instance, the focus is on distortions caused by temporary changes that directly impact prices. Changes to value added tax (VAT) tend to create one-off jumps or falls, which are sometimes later reversed.

As part of government efforts to stimulate demand, we have seen several countries use temporary tax cuts which have distorted their countries’ inflation figures. The most notable is Germany, where its main rate of VAT was lowered from 19% to 16%, and the reduced rate cut from 7% to 5% from 1 July to 31 December 2020. The change caused Germany’s headline HICP annual inflation rate to fall from 0.9% to zero between June and July.

Europe’s statistics agency, Eurostat, publishes HICP inflation rates that remove the impact of changes to taxation. Interestingly, while headline HICP inflation in the eurozone is currently -0.3% year on year (y/y) as of November 2020, when stripping out the impact of tax changes, headline inflation would be +0.3% y/y – a 0.6 percentage point difference (table 1).

Germany is one of the main causes for the drag for the eurozone, as Germany’s inflation rate would be +1.4% rather than the current actual rate of -0.7%. Austria has also seen a large distortion; unlike Germany which cut VAT on all goods and services, Austria delivered a larger cut, but only for restaurants, cinemas and other hard-hit service sectors.

As most of the tax changes made are temporary in nature, not only will the fall in inflation not be repeated, but there will likely be a sharp rise in early 2021 as VAT returns to previous levels. Interestingly, it appears that German firms did not pass on all of the reduction in VAT to customers. This is why the line on chart 3 – that shows inflation using constant tax rates – rises from the point in the divergence with the headline rate. This suggests that these companies wereconfident enough in their pricing power to effectively raise their price excluding VAT – a positive sign for those worried about deflation.

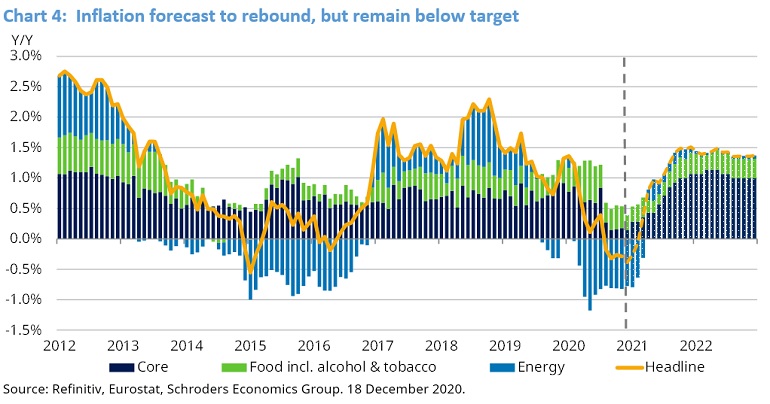

Drag from energy markets

In a similar fashion to the temporary drag on inflation from tax reductions, the fall in global wholesale energy prices, particularly in March 2020, is not likely to be repeated. Therefore, as we progress through the second quarter of 2021, the fall in energy prices will drop out of the annual comparison. Moreover, the level of energy prices has been recovering. The price of Brent Crude fell from $66 p/b at the end of 2019 to a low of $19.3 p/b on 21 April. Since then, it has recovered to $52 p/b as of 18 December.

Taking all of the above factors on board, our forecast has eurozone inflation rebounding to 1% y/y by May 2021, before continuing to rise to average 1.3% over the rest of 2021 (chart 4). Headline inflation then stalls in 2021. Although we see a higher contribution from food prices as soft commodities recover, higher unemployment rates than shown today (due to furlough) reduce wage pressures and weaken demand in 2022. We expect it to take another year before the build-up of excess slack in the economy to be eradicated, keeping inflation well below the ECB’s target.

Implications for monetary policy

It was telling when the ECB decided to only increase its quantitative easing programme by €500 billion earlier this month. Though the ECB met the consensus expectations of those economists polled, it left markets disappointed, as government bond yields rose (prices fell) and the euro strengthened against the US dollar. It appears that the governing council had wanted to ensure there was enough support in place until funds from the EU recovery fund can be distributed in the second half of 2021. However, the council clearly did not feel the need to substantially surprise the consensus as it had done with recent expansions of stimulus.

In the near term, we are confident that inflation will rebound to the point where deflation fears will abate. However, given the warning from the deflation vulnerability index, caution is likely to persist. Indeed, the ECB’s inflation forecast does have a recovery in 2021, but not up to its “close to but below 2%” inflation target. This suggests that more monetary stimulus could be on the cards in late 2021, but at the very least, investors should not expect any meaningful rise in interest rates for at least two or three years.