About reading and writing: I find it hard to read in English, perhaps just a little less than I do writing in Spanish–I can’t write in English, really. That is why I often ask for help, for a translation, knowing that small bits of meaning will be lost in the transition from one language to another. It always happens that little variations of tone, and details, may end up vanishing or subtly changing places. So it could very well be that we in Spain misunderstood Wolfgang Münchau when he published a few days ago an article about the incontestable logic of Spaniards rushing to their nearest bank branch and taking out their savings–Santander and BBVA were the only entities on the safe side–after the Cyprus bailout.

Our savings are at risk, he said. But to figure that Münchau seeks to trigger a bank run in Spain or in any other eurozone country would be absurd. The question, then, is: what was the intention one of the most celebrated columnists at the Financial Times? Do lenders in the City need more deposits? Or is it Swiss banks that need them? Or is it the offshore banks under the British crown umbrella? This sounds even more absurd.

Therefore, I am led to conclude that Münchau’s simply attempted to project some philosophical light, again, over the eurocrisis, the European Union’s incongruous structures and its denial to act as a single issuer, while issuing a single currency, before its creditors.

Yet, theoretical reflections must respect the reality. To be sure, the truth is that in the very extreme situation of Spain, the Spanish taxpayers, having to guarantee all bank deposits, this would be impossible. So it would be for any other country. The current guarantees are set to boost confidence among savers, but no one expect them to be implemented. In all modern states, this is how it works because their banking systems have several times the size of their GDP. Would the British Treasury be able to cover a massive run on Barclays, Lloyds TSB or Santander UK?

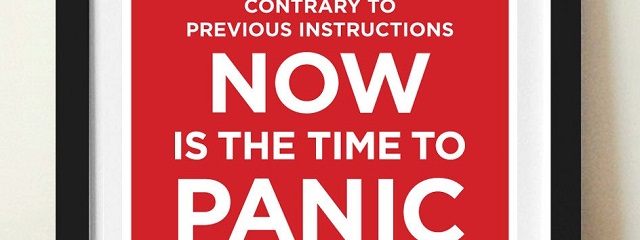

There is no bank in the world, no matter how solvent it is, that could survive such an event. And there is no state that could deal with it when savers and investors panic, dragging down with them the entire financial industry. That is why commentary scaring savers–whether in Cyprus, Spain, Italy or France–smells of negligence at the very least. In Spain, where we had to face capital outflows of over €200 billion in 2012, we are particularly aware of it. Financial journalists, as all journalists, have to be accurate and behave responsibly. Münchau appears to have forgotten that a pretension of aseptic analysis is never enough.

Coincidentally, bank deposits in Spain from non-residents savers increased in February for the second month in a row, which in part compensates the correction of domestic deposits. In January, according to the latest data, Spain received €14 billion in short-term foreign financing, the highest amount since 2011. Münchau should mind.

Be the first to comment on "Münchau’s hazardous panic game"