By CaixaBank research team, in Madrid | According to the Spanish Royal Academy, «rescatar» or bail out in Spanish is to release from danger, harm, trouble or oppression. Given the misgivings that the outcome of the Greek elections might lead to the country leaving the euro, something that would have hindered the considerable financing needs of Spain and Italy over the coming months, the Eurogroup welcomed the Spanish request and decided to provide a loan up to 100 billion euros to recapitalize Spanish banks and thereby dispel at least the other big source of uncertainty in Europe: the capacity of Spain’s financial system to tackle an adverse scenario.

The Eurogroup loan releases Spain from having to provide banks that need capital with such a large sum itself. Moreover, in the hypothetical case of Spain having done this by itself, it would probably have had to resort to the markets.

Given the uncertainty regarding the Greek elections and the capital requirements of Spanish banks, before the bail-out the central government would have had to pay a very high interest rate. For example, the interest rate for 10-year bonds is above 6%, a prohibitive level should it remain this high for some time. Hence the link between the needs of the private sector (banks) and the public sector (central government).

One of the great advantages of the loan is that, in principle, the interest rate set will be significantly lower, between 3% and 4%. However, if this is finally carried out through Spain’s Fund for Orderly Bank Restructuring (FROB), it would be classed as public debt (as the Kingdom of Spain would be the ultimate guarantor) and the interest would be counted as deficit (although a grace period might be given during which no interest is paid for the first few years). Seeing as debt and deficit are actually two of the key variables in determining a country’s solvency, investors demanded higher interest for Spanish bonds (more than 7%) and the risk premium increased to 575 basis points, making the upcoming debt issuances by Spain much tougher.

Within this context, economic activity is still showing signs of weakness. Industry’s Purchasing Managers’ Index has been below the threshold of 50 for more than one year now, indicating that manufacturing is still shrinking, and it is falling away from similar indicators for Italy, France and Germany. Another indicator, the industrial production index, also certified the sector’s difficulties, shrinking by 8.3% year- on-year in April.

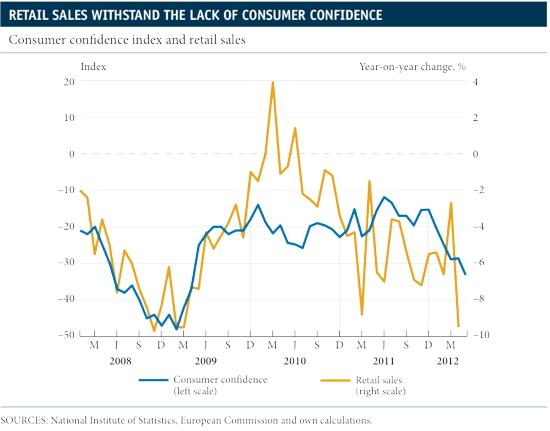

Most indicators, both supply and demand, continued their negative tone and were worse than the previous month. In this respect, of note is the consumer confidence index as well as that for construction, since both fell in May by 5 and 6 points compared with the previous month. This fall places consumer confidence at the level of spring 2009 and is in addition to the drop in retail and consumer goods, down in April by 9.5% year-on-year.

If domestic demand is incapable, at present, of reviving activity, the foreign sector will have to drive growth. To this end, not only does Europe need to specify the details of its financial agreements but also make progress both in the institutional sphere and in the process of fiscal integration. The advances made in this respect will have a positive effect both on growth in Spain and in Europe. According to the Royal Academy’s dictionary, another meaning of the verb «rescatar» is to recoup lost time or opportunities. The time has come for Spain and Europe to recoup themselves.

Be the first to comment on "Spail-out?"