William Chislett via Real Instituto Elcano | Spain is a happier nation than it was a year ago, according to the World Happiness Report (WHR), produced by the Sustainable Development Solutions Network (SDSN), a global initiative for the United Nations, and based on Gallup surveys between 2016 and 2018.

Finland was again the happiest country for the second year running. Five Nordic nations are in the top ten. They all have a strong social safety net, high quality education systems and a commitment to closing the gender gap. War-torn South Sudan is the unhappiest.

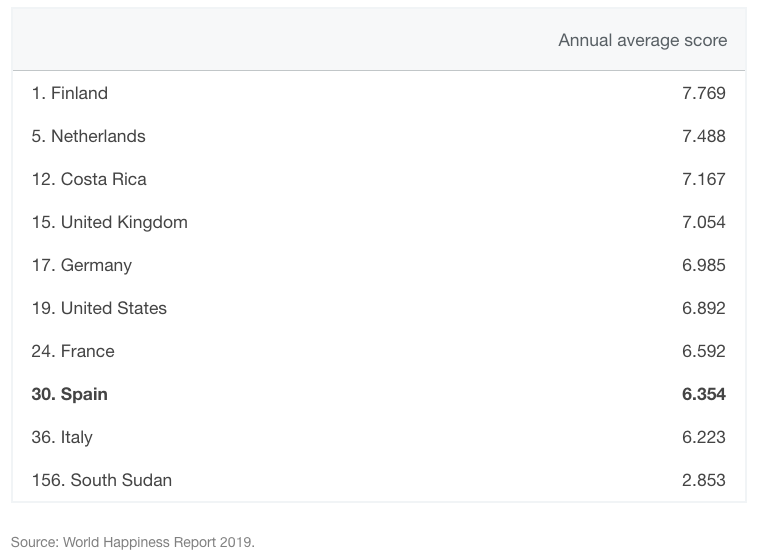

Spain is ranked 30th out of 156 countries, with an average score of 6.634 out of 10, up from 36th place in the 2018 report with 6.310 (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Ranking of Happiness 2016-2018

Ranking happiness might seem a futile exercise. Afterall, happiness is not something that is tangible, although we all know it when we feel it, and that can be objectively measured in the way that, for example, a country’s economic output (GDP) can be quantified.

Money does not necessarily bring you happiness, nor does the lack of it automatically bring you misery. There are plenty of unhappy millionaires and lots of happy poor people. As the Beatles sang, ‘Money can’t buy me love.’

Happiness is relative; there is always someone happier or unhappier than you against whom you can define yourself.

People do not automatically become happier with economic development. This was shown in the Arab Uprising countries where GDP was increasing but the ratings of their lives trended downward ahead of the unrest.

The WHR spurns the usual statistics for measuring wellbeing/happiness –GDP, household income and unemployment– because they focus on purely material issues such as what people spend, how much they earn and whether they are employed, as these metrics do not in themselves show us happiness. Economic growth alone has ceased to be the holy grail for happiness as it often creates new problems.

Instead the WHR weighs six variables: GDP per capita, social support, healthy life expectancy, freedom to make life choices, generosity and corruption levels. The data is compiled from the Gallup World Poll, which uses a measure called the ‘Cantril ladder.’ Survey respondents are asked to place the status of their lives on a ‘ladder’ scale ranging from 0 to 10, where 0 is the worst possible life and 10 the best possible.

The aim of the WHR is to encourage governments and individuals to shape policies and life choices with greater wellbeing in mind.

The economist Alan Krueger, one of Barack Obama’s senior advisers, who died this month, was a prominent expert in ‘subjective wellbeing.’

The WHR’s sub-bars show the estimated extent to which each of the six factors contribute to making life evaluations higher in each country than they are in Dystopia, a hypothetical country that has values equal to the world’s lowest national averages for each of the factors and is used as the benchmark against which all countries can be favourably compared. No country performs more poorly than Dystopia.

Per capita income in the United States is high and the economy is buoyant, but the country is ranked 19th in the latest WHR, down from 13th in 2016, substantially below most comparably wealthy nations. Life expectancy there is declining, suicides are up, there is a major opioid crisis, income inequality is greater and confidence in government has fallen.

Except for its 10th place ranking for income, the US does not rank in the top 10 on the other measures (12th place for generosity, 37th for social support, 62nd for freedom, 42nd for corruption and 39th for healthy life expectancy).

Spain, in comparison, ranks 30th in income, 50th in generosity, 26th in social support, 95th in freedom, 78th in corruption and 3rd in healthy life expectancy .

The high happiness of Costa Rica (ranked 12th), above that not only the US but also the UK and Germany, might seem odd. The country is considered the ‘Switzerland’ of Latin America because of its democracy, peace, relative lack of crime and better social conditions. Its happiness is also explained by the importance of the family and other supportive relationships.

Such relationships are also important in Spain, a sociable society which looks after the elderly and rarely places them in homes and makes a great fuss of children. Spain’s own surveys show that despite the still high unemployment and a worsening political situation (April’s general election will be the third since 2015), its citizens are generally content.

The same goes for the more than 5 million immigrants in Spain. The happiest countries also tend to have the happiest immigrants.

*The original piece was published by Real Instituto Elcano. You can read it here.