*This article was originally published by Fair Observer.

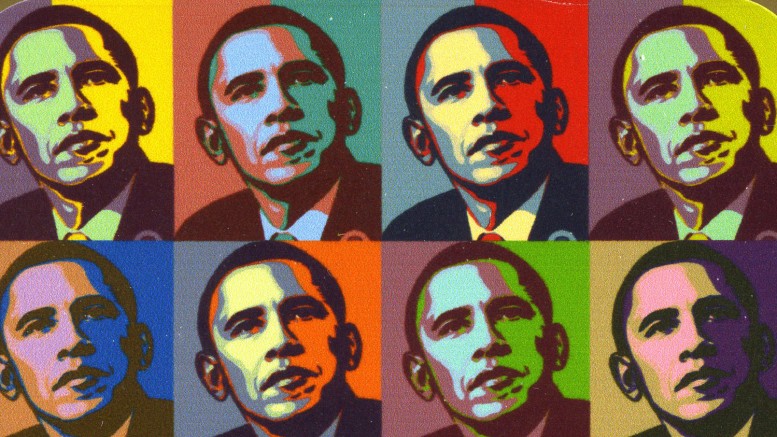

Jarno Lang | Obama is not only a pop-cultural phenomenon, but also a pragmatic leader. His successor will have to deal with a worldwide net of dependencies.

At the end of his eighth and final address at the annual White House Correspondents’ Dinner, US President Barack Obama pulled a “Kobe Bryant” when he dropped a microphone at arm’s length with the words, “Obama out.”

It is references to popular culture like this that constitute a huge bulk of Obamamania with younger people globally, amongst whom he will be sorely missed—though that is certainly not the only reason to look back at the last eight years with some wistfulness, as David Brooks first put forth earlier this year.

When Obama won the presidency in 2008, he entered the international stage with thepromise of change from unilateral to multilateral politics and from Western-centric to culturally sensitive approaches in international relations. Already in the early days of his first term in office, this naive longing for change shifted more and more toward disappointmentfor the left in America, while conservative political circles seemed happy to observe the failing of an open-minded political reform process.

Now, in the middle of the presidential primaries in the US, the two most likely opponents in November’s elections are probably the two least popular candidates of all time in the history of American elections. What a change in comparison to 2008 when Obama had very favorable approval ratings on the domestic front (over 70%) and overseas (e.g. over 90% in the Philippines).

Reasons, of course, are manifold. First, since then a lot has changed in global and domestic politics. In the US, as a starting point, while Obama was fiercely welcomed by the liberal part of the electorate, he himself became the target of hate of staunch right-wing conservatives. This, in turn, meant the Republican Party has tried to deny President Obama all potential political successes.

In domestic politics, this translated into inflexible fundamental opposition by the Grand Old Party (GOP) against the course to overcome the financial crisis, support for health care reform and the closure of Guantanamo, just to name a few. Globally, the wars in the Middle East, the Arab Spring, and unrest in Georgia and Ukraine, together with Russia’s aggressive stance in all these matters, left the Obama administration little choice other than to shift its focus away again from the Asia Pacific toward the “Old World.”

All in all, the world of today has become a different one than it was in the first decade of the 21st century. NATO leaders have described contemporary tendencies as a return to the great power politics of the 20th century with different means.

Ironically, this can be observed in a region where Obama intended to turn America’s interest to, but that had been otherwise largely neglected by his predecessors: the Asia Pacific. The struggle for zones of influence between China and the US is reaching heights that are similar to the historical American-Russian diplomatic standoff following World War II. During the Cold War, Southeast Asia was as much a ground of ideological, political and economic struggle as was the Middle East and eastern Europe, with battles in the form of proxy wars that were actually waged in Indochina.

Today, if anything similar would ensue in the Asia Pacific, such as a second war between the Koreas or an armed conflict in the South China Sea over land and sea ownership between China and its Southeast Asian neighbors, this would be far from a proxy war, but a conflict in which consequences would also be felt in the “Old World.”

Together with the problematic political situations in Ukraine, the Middle East and South Asia, and potential troubles in South America and Africa due to climate change and social unrest, the post-Obama administration will have no easy task ahead. It will first have to decide whether it wants to follow the previous administration’s foreign policy path of pragmatic internationalism or whether to turn to an age-old dilemma of whether isolationism or interventionism is the right choice.

After that, on the second level, all the issues hinted at above will demand individual analysis and care. In a way, although the frames and conditions are different, the US has similar decisions to make as it did in the second decade of the 20th century, when the country’s administrations were at a crossroads and had to decide on America’s involvement in the world.

President Obama’s two terms in office were thus not a new beginning, but a period of transition. Many a comment has already been drafted decrying them as an era of false promises or missed opportunities, depending on the authors’ political backgrounds. All in all, the record of the Obama’s administration certainly hosts deep disappointments and hope for change. But more than anything else, it holds many lessons.

NO MAN IS AN ISLAND

Whatever the younger generation or Barack Obama himself thought when following or proclaiming an audacity of hope, it has become clear that one person—despite being the most powerful national leader of the world—cannot, against fundamental domestic and foreign antagonism, change the course of international relations alone. Every political decision maker is part of a historical, political and sociocultural net, which he or she can influence but only to the degree all the other factors allow him or her to.

The next US president will have to face a net of dependencies, in which the other poles and factors have become stronger than at the end of the 20th century when America was, for a short period of time—at least in perception—the only superpower. Today, omnipotence, even if it ever was anything else, is an illusion and, following the words of late German Chancellor Helmut Schmidt, “people with visions should go see a doctor.”

Thus, as we are nearing the US presidential election in November, one thing is clear: We will not get a second pop-cultural phenomenon like President Barack Obama. However, we should hope for a candidate who acknowledges this worldwide net of dependencies, and an individual who is willing and able to follow Obama’s general path of pragmatic internationalism.

*This article was originally published by Fair Observer.

*Image: Mel McC