WASHINGTON | For the finance historian, Pulitzer Prize and hedge fund adviser Liaquat Ahamed, Benjamin Strong, the man who presided over the New York Federal Reserve from 1914 to 1928, is

“the inventor of the modern central bank. When we see Ben Bernanke or, before him, Alan Greenspan, or Jean-Claude Trichet or Mervy King describe how they try to strike a balance between economic growth and stability, the spirit of Benjamin Strong flies over them.”

Ahamed isn’t the only economic historian who has been fascinated by Strong. Charles Kindleberger, author of the classic “Manias, panics and crashes” says Strong was one of the few American political leaders concerned about the situation in Europe. Had he not died in 1928, the Great Depression would have probably been easier, Kindleberger believes.

The truth, however, is that since 1928, central banks more or less follow Strong’s model. Before him, the key was to maintain the value of the currency, which meant preserving the gold standard at almost any cost. Strong was the first to introduce into the equation growth, inflation and capital flows. In practice, he reduced the importance of the gold standard in the US –what is a real contradiction with the US fixation on keeping it in the international system.

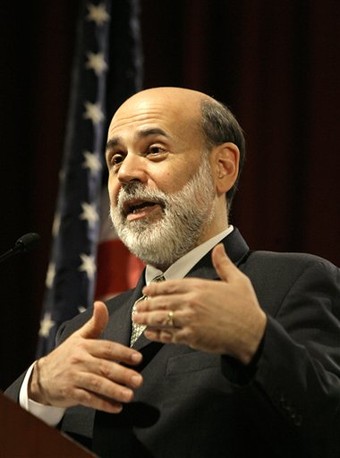

Some 83 years after Strong’s reign and 97 since the Federal Reserve System was created, Ben Bernanke may be carrying out the biggest revolution in the US central bank, an institution that, like those in its category, is not noted for its innovative capacity. But since he took office, Bernanke has imposed a style characterized by three elements:

1) A clear communication policy. This is not without merit in someone like the governor of the US central bank, famous for its inability to interact socially, what has sometimes led to glaring blunders like when he put purple socks for a reception in the White House. Not to mention his shyness –his voice literally trembles when giving press conferences, 2) A major concern for the price of assets. Until now, the Fed, like other central banks, did not take into account anything more than the prices of goods and services, 3) A much more unorthodox policy based on market intervention to ensure that the US does not end up facing a lost decade like Japan after the bursting of its bubble in real estate –a lost decade that many believe is coming towards Europe, as long as Italy can be stabilized.

1) A clear communication policy. This is not without merit in someone like the governor of the US central bank, famous for its inability to interact socially, what has sometimes led to glaring blunders like when he put purple socks for a reception in the White House. Not to mention his shyness –his voice literally trembles when giving press conferences, 2) A major concern for the price of assets. Until now, the Fed, like other central banks, did not take into account anything more than the prices of goods and services, 3) A much more unorthodox policy based on market intervention to ensure that the US does not end up facing a lost decade like Japan after the bursting of its bubble in real estate –a lost decade that many believe is coming towards Europe, as long as Italy can be stabilized.

These three transformations have been confirmed during the last two months as members of the Federal Open Market Committee –the body that decides interest rates– made clear their views on how to achieve one of the central bank’s three mandates: full employment (the other two, which are price stability and long-term low interest rates are already in the bag). The Keynesian members of the Fed –like Janet Yellen, wife of Nobel economics and father of the ‘Behavior economics’ George Akerloff– have said that the US central bank should carry out a new money-printing operation with which to buy financial assets.

In other words, a third wave of ‘quantitative easing’ or, as is known in the US, QE. That is, we would be facing QE3. It will probably begin in January, just when October’s ‘Operation Twist’ finishes, yet another unorthodox measure: short-term public debt issues and purchases of long-maturity bonds so the first ones see an interest spike and the second gets exactly the opposite results (ie, lower long-term rates, something very important in the US, where two thirds of the mortgage bonds are referenced to over-10 year Treasuries). Thus, financing the economy turns out cheaper, although the change destroys small banks, which derive much of their funding from short-term borrowing and long-term lending.

The more orthodox members of central bank’s board, like Richard Plosser, warn of the ‘stagflation’ danger, that is, low growth –the possibility of a recession seems to have disappeared since October, unless a catastrophe happened in Europe– and high inflation. A throwback to the seventies.

The truth is that until Bernanke spoke on November 2, 69% of traders surveyed by Bloomberg took for granted that there would be a QE3. But then, the president of the Fed gave a press conference with his distinctive shaky voice and mentioned nothing.

This gave rise to two interpretations: one, that although the QE3 is a viable option under certain conditions, the head of the US monetary policy

“provided no evidence that these conditionsar ein place” (Eric Green of TD Securities)

and other, that

“the foundations of the QE3 have already been built and it is only a matter of choosing the right time, unless the housing sector recovers sooner.”

No one expects that, so far.

The first QE meant buying assets based on other assets, that is, private sector debt. The second bought public debt. The third would buy –or will buy– mortgage debt. It would be a new twist from this unlikely revolutionary Ben Bernanke, whose most revolutionary habit according to rumours is his penchant for playing chess while his wife watches movies of Carlos Saura.

Be the first to comment on "QE3 and the revolutionary Mr Bernanke"