A buyback is the repurchase by a company of its outstanding shares in the stock market. They can have a variety of intentions for doing that, but the most immediate impact is to keep the share price higher than it would be without this additional demand. In this way, the shareholders are happy and the company’s bosses pocket a higher bonus.

Cullen Roche says there are lot of myths surrounding this practice, and it’s accused of evils of which it is not the cause, but is more an effect: it’s just a procyclical reflection of the big profits built up by the companies. However, the majority of them consider it to be a “conspiracy” against investing in productive capital, a way of holding on to resources which become part of a company’s financial assets, but don’t increase the market’s capacity. They also consider the buyback practice to be one of the reasons fuelling high stock market levels.

In the first graph, we see the US companies’ record high profit levels, compared with corporate investment as a percentage of GDP, which remains at record low levels.

There is no doubt that companies have no desire to increase capacity. But to what extent does the buyback practice represent an important deviation from investment? If there were no profits, there would probably be no buyback which, at the end of the day, is no more than a derivative arising from a company’s excess of available funds. In other words, the buyback doesn’t increase these funds, only redistributes them.

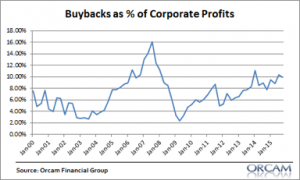

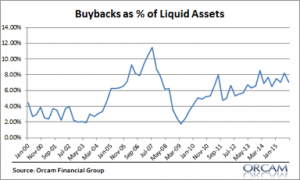

In 2009, at the worst moment of the crisis, before the economy began to turnaround, the buyback was only 2% of profits. Since then, it has increased to 10%, representing 8% of liquid assets, as shown in the second graph.

What impact can this have on the overvaluation of the markets? Needless to say, it’s not the main cause. The stock market is trading at high levels because profits are high. And profits are high because financing is cheap. The economy has grown and companies have increased their sales. But neither low interest rates nor profits have encouraged investment. This is the main reason for the stagnation eight years later.

![Buybacks Are More A Symptom, Not A Cause [UNSET]](http://thecorner.eu/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/UNSET-300x199.png)