The British economy has absorbed Brexit well, showing that the Cassandras who announced that the end of the world was near were not only exaggerating but in fact boosted the vote to leave the European Union.

One of the reasons for this soft landing is the pound’s devaluation, which can be seen in the graphic below.

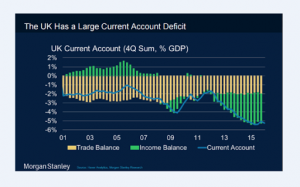

But this is just the start of what the UK’s huge current account deficit needs, as we can see in the following graphic.

A current account which is 5% of GDP is not an imminent crisis for a country like the UK. But according to the IMF, a more acute devaluation of the pound than we have witnessed up to now is required to correct this.

And we will no doubt see this. And this is a problem for the Eurozone, which is struggling hard to pull itself out of deflation. It has unfurled all the sails of monetary policy (QE, negative interest rates, etc), so a revaluation of the euro against the pound would be in stark contrast to these efforts. In the following graphic you can see the expectations for infla(defla)tion in the Eurozone, which is making the ECB lose the battle.

As if none of the ECB’s moves had any impact at all on the expectations for prices.

Added to this are the deflationary forces coming from China, with the devaluation of its currency and its internal devaluation – or deflation – as Ambrose Evans-Prichard says. I am using his graphics.

All this begs the question how Spain can be doing as well as the government says – massive growth, foreign trade surplus, job creation (or, better said, micro job creation) – if Europe is stagnating, with deflation and negative interest rates…Where are the strengths coming from? There is either some creative accounting going on, or there is a pull from public demand; but this is internal demand, which would have an impact on the external deficit. Has the decline in salaries had such an effect on competitiveness? Because productivity is definitely conspicuous by its absence, which is logical if employment is growing at the same pace as GDP (increase in productivity=increase in GDP=increase in employment, aprox.). So unit labour costs have not improved very much, as far as I know.

Are we living on an island where we are not affected by the problems of others? Have we solved our long-time structural problems by containing wages, by creating temporary or part-time jobs, hourly contracts, subcontracting, social security contributions which are a multiple of the people who start work, etc? The government boasts that 80% of current contracts are stable, but what it doesn’t say is that 80% of these should be thrown in the rubbish bin. Is it really possible for Spain to be doing so well when Europe is doing so badly?

Can Spain grow at twice or three times the rate of other European countries with a fixed exchange rate? I was taught this was not possible. And I don’t think they lied to me. The issue is that given the strength of the economy, internal interest rates should be increasing. But they are declining thanks to the fact they are “made in” Frankfurt.

I have the well-founded suspicion that what has really boosted the economy has been internal demand, pulled along by public spending in consumption and investment, financed at very low rates thanks to Draghi’s policy of buying huge amounts of government bonds. I suspect this because public consumption and total investment (I don’t have figures which separate public and private investment) have followed the same curve since the start of 2015. This indicates that the contribution to the total from public investment is significant. But this has stopped functioning because Spain has had a caretaker government since December 2015. Public spending has almost stopped growing.

Up to now, the strength of domestic demand would explain the dynamic trend in imports, much more intense than in exports, which sooner or later will cause problems for the external deficit…Although the halt in public spending suspends this statement.

As far as the external balance goes, supposedly we export a lot, but the fact is that we have imported more in the last five quarters. An anecdote: they say we export a lot of cars, but I see a great deal of imported cars on our streets…In any event, if imports are growing more strongly than exports, then domestic demand is strong. Until when?

The pound’s weakness is already a problem, particularly for Spain, and if this is prolonged it will be an even bigger one.

But in my opinion this is not the urgent problem. I think this is going to be Brussels’ increasing anxiety to meddle with our deficit. This may be in a mild or tough way, but the halt will be painful.