One of the most objective measures for judging whether the stock market is expensive or cheap is the dividend yield. The dividend is paid out, profits are only recorded. In reality, in the long-term, the value of a company is no more than the current value, with a discount rate representing the level of risk of the investment, all the dividends it will pay in the future, all the money it will return to shareholders.

When the dividend yield offered by the stock market is clearly higher than the real return offered by fixed income, then we are looking at attractive equity valuations. Due to its very nature (sales, and with them profits and dividends, usually reflect price rises), investing in the stock market is the most natural protection against inflation.

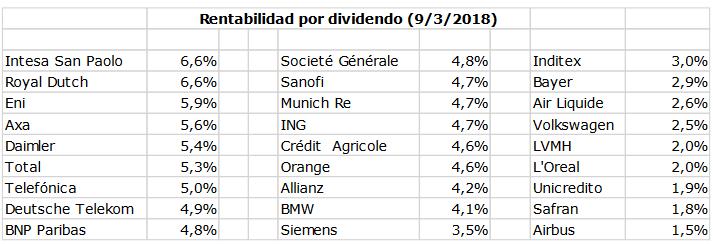

At the moment, and taking into account as a reference the dividend yield, the main global stock markets offer real returns which are superior to those of long-term sovereign bonds. In the case of the US, the differential is moderate (the dividend yield of the S&P 500 is close to 2% compared with a real traded 10-year rate in the TIPS of 0.7%). In the Eurozone, the excess dividend yield versus the real return on sovereign bonds is much higher (3.4% for the Euro Stoxx 50 compared with 0% on Spanish sovereign debt or -0.7% on German 10-year inflation-linked bonds).

The majority of European companies have significantly increased shareholder remuneration via dividends. In 2017, most of them increased their dividend payment compared to a year earlier. As an example, 34 of the 40 biggest French firms, those which make up the CAC40, have increased dividends over the last year.

The financial crisis of 2007 fuelled the reduction, or even put the breaks on, dividend payments in the case of a good number of companies, particularly those in the financial sector or those with a lot of debt, like the telecoms operators. But despite the deep crisis of 10 years ago, a reasonable number of big companies have been able to maintain or increase their dividend payments without any interruption. In particular, this has happened with big companies in the industrial and consumer sectors which have a global presence (Bayer, Sanofi, Air Liquide, L’Oréal, LVMH, Inditex, Siemens…).

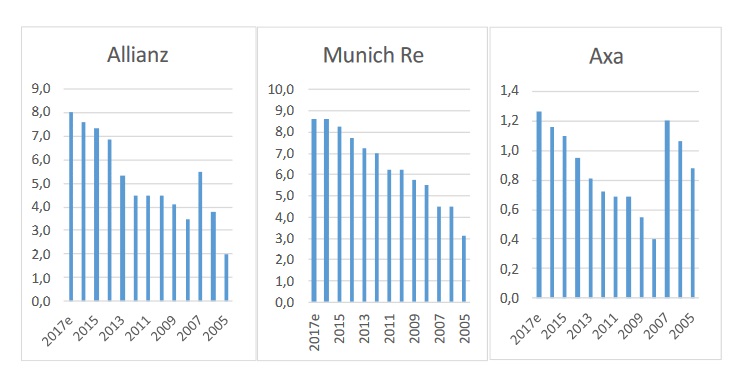

The biggest dividend yields can currently be found in the insurance and oil sectors. From 2008 to 2017, the three main Eurozone insurers represented in the Euro Stoxx 50 index, have increased their dividend payments in a sustainable way, year after year, and offer a return at current prices which varies between 4.3% for Allianz and 5.6% for Axa.

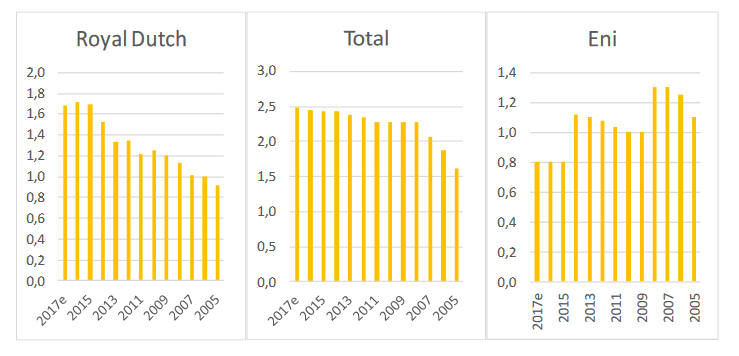

In the oil sector, the two biggest firms, Royal Dutch and Total, have been able to maintain a policy of rising dividends, or in the worst years a constant dividend measured in dollars, despite the significant declines in oil prices. The Italian oil company ENI is the only one which has had to make a slight cut in its dividend in the last few years. But in any event, the dividend yield they offer at current prices is very high (6.6% for Royal Dutch, 5.0% for ENI, 5.3% for Total). As oil prices stabilise at levels close to or higher than 50 dollars/barrel it’s reasonable to expect that this yield is maintained or rises slightly, which in principal should ensure that minimum trading levels are no lower than the current ones.

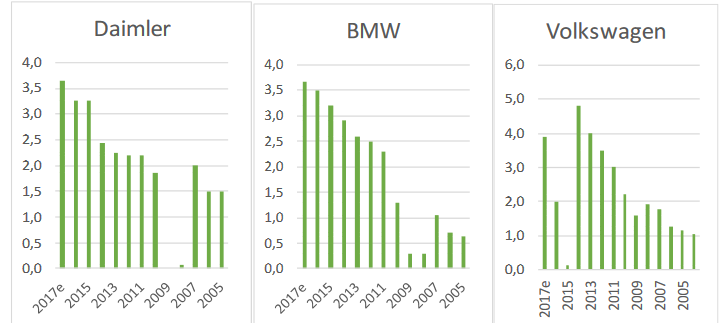

The automobile manufacturing sector was affected by the 2007 crisis, due ot its more cyclical nature. It was forced to cut its dividend payment substantially for a couple of years. But in the last seven years, Daimler and BMW have increased their dividend in a sustained way, pushing it to levels which are double those before the crisis. The diesel scandal (with the consequent multimillion fines in the US) forced Volkswagen to cut its dividend, which it is now gradually recovering. Daimler’s dividend yield is one of the highest in the Euro Stoxx50 (5.4%), BMW’s (4.1%) is clearly higher than the average for the index (3.4%) and Volkswagen is slightly below (2.5%).

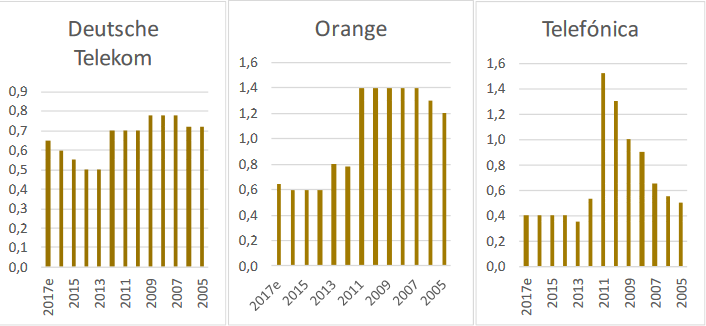

High levels of debt, combined with the huge need for investment in networks and regulatory pressure on prices are the three factors which have led to the big telecoms operators having to reduce their dividend payments. And they are still clearly below pre-crisis levels. In any event, the big correction in the stock market has meant that at current prices, the dividend yield they offer is very attractive, at levels close to 5%.

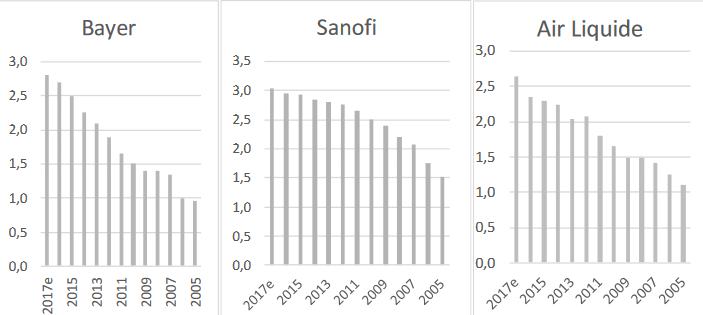

Despite the crisis, the chemical-pharmaceutical companies have managed to constantly increase their dividend, without changing their traditional moderate policy. Year after year, companies like Bayer, Sanofi and Air Liquide have increased shareholder remuneration.

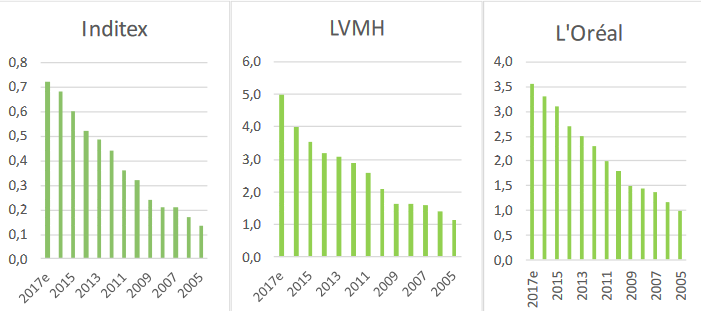

The big consumer sector multinationals, like Inditex, LVMH and L’Oreal have also increased their dividend payments without any interruption. Currently they are at levels which are more than three times those paid out before the crisis.

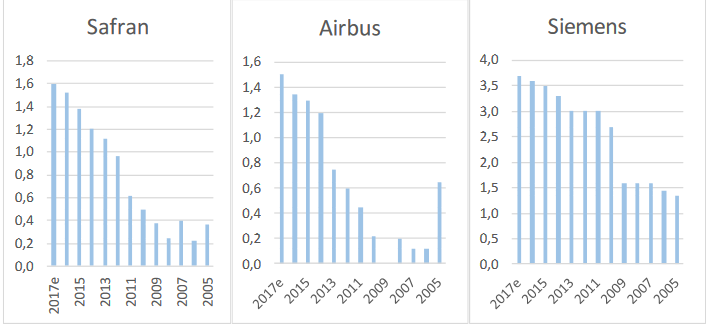

More affected by the global recession of 2008, the big industrial companies in the Eurozone had to moderate (or even suspend in the case of Airbus) their dividend policy for a couple of years, but have recovered it substantially over the last seven years. Siemens and Airbus now pay dividends which are double those offered before the crisis, and in the case of Safran, it has quadrupled its dividends.

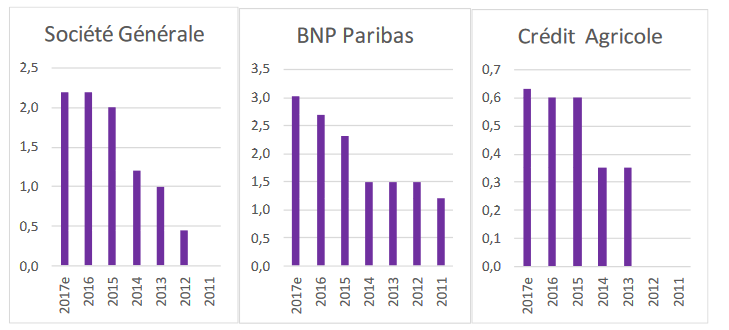

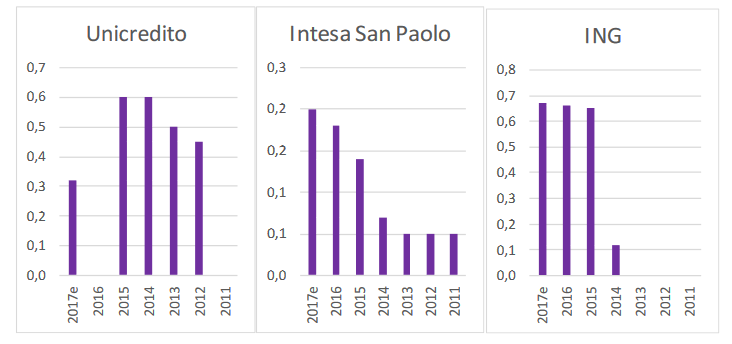

With some honourable exceptions (BNP and Intesa), the banking sector had to interrupt its dividend payments (in many cases scrip dividends cover up this interruption) for quite a few years after the financial crisis broke out. And with the odd exception (like Unicredit which recently made a capital hike) the banks have renewed their policy of increasing dividends in the last three years.

So overall, we can say that those companies most exposed to a global market, the big European leaders in the consumer and industrial sectors, have practically not interrupted their policy of increasing dividends in any year, despite the big crisis of 2007. And that the financial companies and the former monopolies (notably the telecoms operators), with a business which is more limited to the European market, saw their dividend policy altered over a period of between three and five years since the start of the crisis. But they have started to increase their dividend again, raising it to levels which are clearly attractive, at current market prices, compared to fixed income.