LONDON/MADRID | Finance-wise, Italy is unnerving some of its neighbours in the periphery of the euro zone. Particularly in Spain, government officials wonder aloud about the unfairness of the whole situation: while yields of the Spanish 10-year sovereign bonds time and again cross the 7 percent frightening barrier, Italy managed last week to sell €5.25 billion in debt of various maturities at much lower interest rates in most of the occasions than in its previous sales.

LONDON/MADRID | Finance-wise, Italy is unnerving some of its neighbours in the periphery of the euro zone. Particularly in Spain, government officials wonder aloud about the unfairness of the whole situation: while yields of the Spanish 10-year sovereign bonds time and again cross the 7 percent frightening barrier, Italy managed last week to sell €5.25 billion in debt of various maturities at much lower interest rates in most of the occasions than in its previous sales.

The ratings agency Moody's had just downgraded the State's debt to Baa2 from A3 only hours before the Italian auctions took place. Italy sits now at two steps from the no-investing 'junk' category, which is to say that the country's public finances have continued worsening under the command of president Mario Monti and his technocratic cabinet. Nevertheless, the government paid Friday July 13 a 4.65 percent yield on €3.5 billion in three-year bonds, less than in May this year, and less than the 5.3 percent paid in the previous operation.

One auction's yield does not immediately push up the entire costs of the credit a country extracts from the markets, so when Madrid explains that Spain has no solvency issues and, even in slightly a bullfighter fashion, that the government can endure harsher yields, analysts agree this is true. Which brings little relief to the mounting tension within the euro area to support States whose access to international credit is drying at high speed. And Italy will not escape this fate, eithe

r.

JP Morgan's global equity department, for instance, believes Spain and Italy travel on the same train and the markets could close their doors to both countries in a matter of weeks or a few months.

Would it take Italy's president Monti by surprise? It should not. According to JP Morgan's figures, Italy faces about €200 billion in maturities each year during at least the next three years. Then, it must be added the sum of €30 billion annually, too, to finance its yearly deficit. For Spain, the numbers are €50 billion and €60 billion.

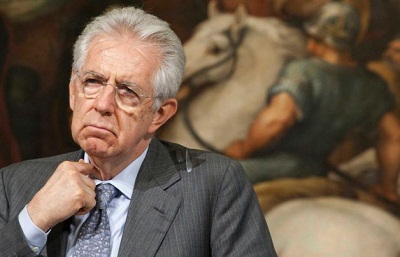

Monti, the non-partisan economist, independent from Italy's political parties, has somehow been hiding behind the mess professional politicians have made elsewhere. It is not his fault, but the lack in progress in further labour reforms, just to name one, is. Unemployment grows, domestic consumption contracts and depression has become a very real threat.

Sooner than later, the markets will price the facts and Italian bonds will suffer. Monti better doesn't rely on others, namely Madrid, slipping towards accidental policy mishaps and untimely declarations, to which admittedly Spain's government shows an apt proclivity. Before Berlin accepts any debt mutualisation formula and European Central Bank intervention, the financially troubled euro country members, Italy among them, need to prove they understand what is at stake by themselves. Rome, so far, seems to have wasted precious time.