Yoichi Funabashi and Harry Dempse via Caixin | Sino-Japanese relations have been stuck in a political quagmire for over six years. Tensions over the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands have resurfaced time and time again since September 2010, when a Chinese fishing boat rammed two Japanese coast guard ships and its captain was arrested by the Japanese. Japan harbors suspicions that Chinese aggression is aimed at forcing an eventual retreat of the United States from Asia and the Pacific. And China continues to lambast Japan for its failure to face up to its history in the Sino-Japanese wars, as well as its contemporary push toward re-militarization.

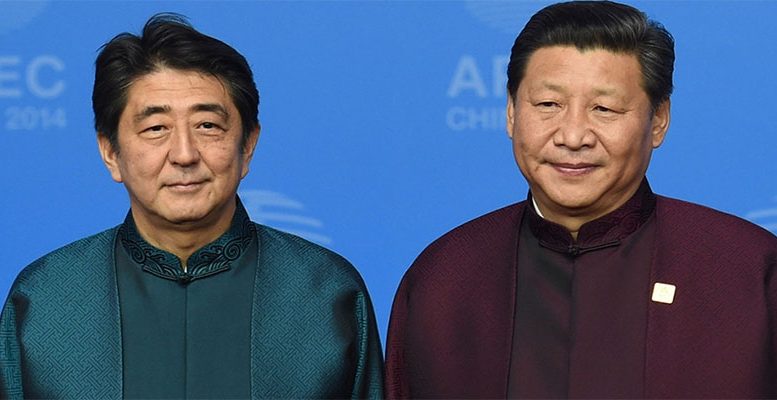

But speculation over a potential rapprochement between the two nations has emerged after Japanese Prime Minster Shinzo Abe’s unexpected declaration that “Japan is ready to extend cooperation (with the Belt and Road Initiative),” in a speech on June 5. The statement was preceded by Toshihiro Nikai, secretary-general of the Liberal Democratic Party, representing the Japanese government at the Belt and Road Forum and a visit from China’s top foreign affairs official, Yang Jiechi, to Japan. Tokyo has sounded out the possibility of a trilateral summit including South Korea in July 2017 (although that plan has now been postponed by Beijing) and reciprocal state visits by Abe and Chinese President Xi Jinping provisionally set for late 2018.

Abe previously tried to reset Japan-China relations in 2006 during his first term as prime minister, after their deterioration under his predecessor, Junichiro Koizumi. But what has motivated Abe to again extend an olive branch now?

U.S. President Donald Trump has been a factor in two ways. Firstly, U.S.-China relations have struck upon a kind of high-risk, fragile reframing, mainly because Trump is prioritizing a solution to the problem of North Korea through Beijing. Abe has joined U.S. calls for China to increase pressure on North Korea. Undoubtedly ensuring peace on the Korean Peninsula would help drive the stabilization of Sino-Japanese relations. In the long term, the most promising path to a solution of the North Korea issue — coordinated pressure facilitated by five-party talks — demands the improvement in relations between Tokyo and Beijing, in addition to relations between other key players.

Secondly, uncertainty over the regional role of the United States under Trump makes it imperative to be proactive in improving relations. In the absence of a comprehensive regional strategy, Washington’s commitments to Asian security are in doubt. Regional economic integration has been put at risk by the Trump administration’s protectionist policies and rhetoric, and its withdrawal of the United States from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). Trump’s transactional approach to foreign policy makes the United States’ playing China off against Japan a real possibility.

Although Tokyo, which is pushing forward with TPP-11, is hoping that the US will come back at some point to this multilateral deal, there is a growing, sobering skepticism in policy circles that it’s unlikely to return any time soon. Tokyo has begun serious contemplation of a clean-slate foreign policy absent of U.S. primacy. In the case of a recalibration like this, no relationship would be more important to stabilize than that with China.

To promote trade liberalization and open regionalism, feasible options for Japan are the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) — which already includes China as a member — and TPP-11, which should allow for Chinese participation on the condition it lives up to its high standards. Other member countries, such as Singapore and Malaysia, will only proceed with TPP-11 if it does not affront China.

The Belt and Road initiative is another area for Abe to seek to stimulate the Japanese economy and gain diplomatic capital with Beijing. Consequently, Tokyo’s overturning of its reservations about participating in the initiative has been in the spotlight. There is a line of thought that only involvement can lead to influence over the standards of Belt and Road projects, as well as win-win benefits for Japanese companies.

But Abe’s proposal to cooperate with the initiative came with strict caveats: “It is critical for infrastructure to be open to use by all … [and] for projects to be economically viable and to be financed by debt that can be repaid,” Abe said. Direct engagement with the Belt and Road was prefaced by emphasizing rules regarding state-owned enterprises agreed to by Vietnam in the Trans-Pacific Partnership and book-ended by positing the benefits of Japan’s high-quality infrastructure partnerships. Abe’s offer was tentative, informal and critical.

Three big challenges lie ahead. The first is whether Abe’s assent to Beijing’s strategic geoeconomic program to win geopolitical cooperation is sustainable. Criticism stemming from values-based diplomacy could halt the warming. The second is a U.S.-China “deal” over North Korea. On one hand, a breakdown in relations would raise the possibility of military conflict that would hugely complicate China and Japan relations. On the other hand, success would likely see Japanese and South Korean concerns bypassed. The third challenge is the long-held, mutual and overwhelmingly negative state of public perception. In BBC opinion polls, only 3% of Japanese citizens and 5% of Chinese citizens view each other positively. Meaningful reconciliation is a long-term process of strategic alignment and compromise, not just sudden realpolitik play without grassroots groundwork.

Despite Abe and Xi lacking natural personal chemistry, they are strong leaders who give priority to their domestic economies. This adds plausibility to the prospect of their seeking a mutually beneficial relationship based on common economic and strategic interests.