Several factors have combined to slow global growth in recent months, including inclement weather in the US, the drag on Japan’s economy from higher consumption taxes, and the slowdown in China’s property sector. Growth in parts of Europe – and Italy and France in particular – has also been more sluggish than we originally forecasted. Moreover, global trade growth has lagged.

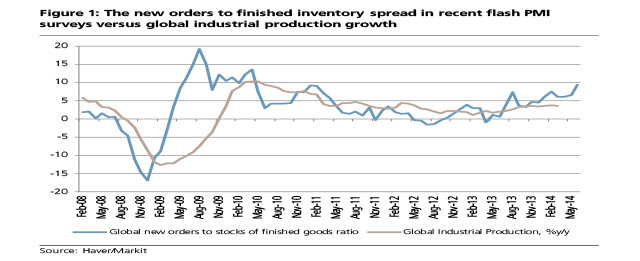

Still, we remain of the view that activity in the world economy will pick up in the months ahead, led by the United States. That is consistent with most leading indicators, including this week’s flash PMI surveys from the US and China (see figure 1 above). In addition, in the US business investment is trending up, household spending and incomes are on the rise, and payrolls continue to expand steadily. Accommodative monetary policies and financial conditions ought to provide support to the world economy as well. Also, fiscal policy has become less restrictive in the US and Europe, which bodes quite well for the global economic outlook.

Still, important risks to the outlook provide a note of caution about the outlook. Prospects for various emerging economies remain challenging, as underscored by our PMI ‘heat map’ below. The unwinding of China’s credit-fuelled housing imbalances, weakness in world trade growth, and the potential for higher US interest rates (as the Fed concludes its tapering) leave many emerging countries struggling to gain traction. Geopolitical instability in Ukraine and the Middle East and its potential consequences for oil prices is a further reason for caution.

Europe’s data has also been soft in recent weeks. The latest PMI readings for Germany and Spain have sustained positive momentum, but the pace of improvement has ebbed elsewhere, notably in France and Italy. With inflation outcomes uncomfortably low, the prospects for nominal GDP growth are a concern. Our European team maintains that the recovery will gather speed and that inflation will drift higher. The ECB’s recent policy easing offers some support. Overall, however, the Eurozone presents a picture of an uneven and tepid recovery.

Generating stronger demand remains the chief challenge for the world economy (and policy makers). Helpfully, indicators of private sector uncertainty in the US and Europe have receded in recent months, which bodes well for confidence and credit demand. Nevertheless, considerable work remains, above all to stabilise Europe’s banking sector, before stronger domestic demand.

A further issue of concern regards a possible escalation of the crisis in Iraq, with attendant risks for the cost of energy. In the past, global growth has weakened as energy prices have spiked.

Indeed, a Brent price of USD115 has proven to be a tipping point for the world economy, as indicated by comparing our global growth surprise index and Brent prices. Oil prices and global growth surprises are typically positively correlated, as stronger growth lifts crude prices. But there are limits to how far oil prices can rise without triggering a growth slowdown, particularly if unexpected supply shocks push prices up suddenly from already high levels. Eyeballing the chart suggests that whenever oil prices have breached USD115 in recent years, global growth has typically taken a turn for the worse.

Simulations on the Oxford Economic Forecasting (OEF) econometric model suggest that an increase of USD 10 in the price of a barrel of oil—driven by supply shocks—will shave around 0.2 to 0.3 percentage points from global growth. Every USD10 per barrel increase in the price of oil typically transfers around 0.5% of global GDP from oil consumers to oil producers. The model assumes—correctly in our view—that the propensity to spend additional income in the oil-producing complex is lower than it is in the oil-consuming complex.

The same simulations suggest that oil-importing emerging countries are typically worse off when oil prices climb. For instance, East European economies such as Hungary, Czech and Turkey or Asian economies such as the Philippines, India and Thailand fare poorly in oil shock scenarios. These economies would suffer a shortfall in growth of between 0.5 and 0.7 percentage points should oil prices unexpectedly climb a further USD 10 from current levels.

Oil-producing economies such as Russia or Norway clearly benefit from higher oil prices rise, enjoying a boost to GDP of up to 0.6 percentage points (Russia) or 0.2% points (Norway). Among large developed economies, the US and Japan are least affected. Prior to the US shale revolution model simulations suggested a negative impact of 0.2 to 0.3 percentage points for very USD 10 increase in the price of Brent. The estimate has dipped to 0.1%. European economies, with higher oil import intensity, are more exposed.

Be the first to comment on "The world’s disappointing recovery"