Brent oil prices are up more than 30% this year and have reached levels last seen in 2014. BoAML’s team on Commodities have revised up their forecasts; they now expect Brent to peak at $95/bbl by the end of 2Q 2019. They also consider the impact on global growth of an even larger and more sustained oil spike. Specifically discuss the factors that could drive oil prices to $100/bbl, and hash out the winners and losers.

What’s driving oil?

The most important near -term driver of oil prices is the supply shock coming out of Iran because of the impending US sanctions. Iran exported more than 2.1mn barrels per day (b/d) last year. The US administration ’ s stated goal is to bring that number down to zero. Although the sanctions are unilateral, they apply to all firms that do business in the US, including shipping and insurance companies. This gives the US leverage to force other countries to cut their imports of Iranian oil.

China and India together account for nearly 60% of Iranian oil exports this year. While Indian refiners got waivers from the previous sanctions, it appears that this time they will comply. Refiners from Europe, Korea, Japan and India have already cut their purchases from Iran, and exports have fallen by 900mn b/d in the last five months. This leaves China with substantial room to increase its purchases from Iran, possibly at below – market prices. However, doing so would further escalate China ’ s trade and broader geopolitical conflict with the US administration. Therefore analysts at BoAML believe China will take a middle course, maintaining its current imports from Iran, defying the sanctions, but not increasing imports. News reports suggest that China is increasing its crude oil imports from West Africa to compensate for import cuts from the US and possibly Iran.

The collapse of the Venezuelan economy is causing further supply disruption. Production in Venezuela has fallen by more than a third from its 2016 level and, barring a brief interlude in 2002, is at its lowest level since the 1940s. Meanwhile US shale producers are hitting infrastructure and labor supply bottlenecks. And with the global economy growing slightly above trend, demand growth is also robust. All of these factors limit the ability of the other OPEC members (notably Saudi Arabia) and Russia to curtail the rise in oil prices by increasing production. Indeed, suppliers are already having trouble keeping up with demand and OECD inventories have been falling steadily. Higher oil prices seem inevitable and, in our view, $100/bbl is easily within reach.

How does oil affect growth?

According to the experts at BoAML, the first -order impact of higher crude oil prices is a transfer of wealth from some countries (net importers of oil) to others (net exporters).

On its own, this does not affect global growth. But we do know that large spikes in oil have preceded economic downturns, including most notably the Great Recession. What gives? There are a few reasons that big moves in oil tend to be bad for the global economy. First, large price moves tend to cause reallocation and uncerta inty shocks, which slow growth, particularly in the short run. This can happen for both sharp increases and sharp decreases in prices. Volatility makes it hard to make business spending decisions that hinge on the price of oil.

Second, purchasers of oil typically have a larger marginal propensity to spend than producers. The shock to real income from higher oil prices would cause consumers to reduce their purchases of many goods and services, not just gasoline.

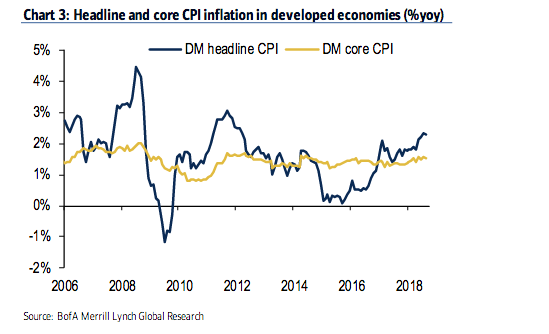

This is particularly the case for large shocks , which are harder to smooth over with savings. Next chart shows the dramatic impact of oil prices on DM headline inflation in recent years, fir st pushing it down to roughly zero — a windfall for consumers — and then pushing it we ll above core inflation more recently.

Those swings are much more muted in EM where many governments regulate energy prices. In the short term, higher oil prices tend to rais e budget deficits in oil -importing EMs, but as prices continue to rise, governments eventually relent and pass the cost through to consumers. We are not at that stage yet.

Of course crude oil manufacturers would get windfall profits from $100/bbl oil. They might spend some of those profits on capex or raise their employees ’ wages. These actions would support growth. But they would also likely spend some of their profits on less economically- productive activities such as share buybacks and larger dividends for shareholders (for public companies) or payments to stakeholders (for private companies). Owners of public and private companies tend to be disproportionately wealthy, and so they have lower marginal propensities to consume. In the case where the oil producers are governments (e.g. the Saudi government) they might simply save their profits. And even if they do some infrastructure investment we would worry about the typical inefficiencies in government spending.

Finally, the countries that stand to lose from higher oil prices have historically been much more systemically important to the global economy and financial markets than oil exporters. This is less the case today due to the shale boom in the US, but it is still true that the Euro area, Japan, China and India stand to lose significantly from a spike in oil prices. Big gains for Saudi Arabia and Russia would not offset the disruption to trade and markets caused by growth slowdowns in most of the major global economies.

The biggest losers

BoAML consider the effect on global growth if oil prices were to rise to $100/bbl at the start of next year and then remain at that level throughout the year. This is admittedly a much stronger assumption than our commodities strategists ’ baseline, but it helps underscore the risks.

As discussed above, many of the large economies including the Euro area, the UK and Japan would be clear losers because they are oil importers. Analysts at the firm estimate that growth in these countries would be depressed by 0.2 -0.5pp next year.

The impact in Japan is likely to be in the low end of this range because robust recent income growth has shored up household finances. By contrast in the Euro area and the UK, saving rates are already very low, leaving households without much buffer to smooth through the i mpact of a large oil shock.

Weakness in developed Europe should exacerbate the shock to central and eastern Europe, although robust domestic consumption and high wage growth could offset some of the negative impact. Other emerging economies that will like ly see weaker growth by a few tenths include India, ASEAN, Chile, Peru and the Dominican Republic.

Mexico recently became a net oil importer after many years as a net exporter. Production in the supergiant oil field Cantarell is declining fast, while gasol ine consumption continues to trend higher, with more than 50% of gasoline imported from the US. As a result, experts estimate that oil moving to $100/bbl next year would reduce Mexican GDP by about 20bp.

In China, the impact on reported growth might be negligible for two reasons. First, petroleum prices are regulated, and state -owned refiners might absorb some of the oil shock, limiting the impact on gasoline prices. Second, growth is already expected to fall to a low 6 -handle because of the trade war (our offic ial forecast is 6.1%). Authorities might be hesitant to print a number below 6% as soon as next year.

Taking the good with the bad

As mentioned above, the surge in shale production has left the US in a better position to handle the oil shock than in the past. The windfall to consumers from the oil price collapse in 2014 -15 resulted in only a mild tailwind to growth because there was an offsetting collapse in energy-related capex.

We would expect the opposite to occur if oil prices were to spike, with the above -discussed caveat that shale investment is running into bottlenecks. Taking everything into account, we would expect a negative impact of roughly a tenth on growth next year.

The story is similar for Australia, where the recent ramp up in LNG production means higher oil prices would now have a positive impact on terms of trade. Over the course of the year, the negative shock to consumption would likely be offset by the boost to company profits, which would support investment and wages.

Thus the net effect on growth would be close to zero. The growth impact of an oil spike is also expected to be negligible in Brazil. This is intuitive since net imports of oil are close to zero. The negative impact on consumption would be roughly offset by stronger industrial production.

The biggest beneficiaries

Of course oil exporters would be the clear beneficiaries if oil prices were to keep rising. Assuming no new sanctions, BoAML would expect 1.8% GDP growth in Russia next year, compared to their baseline of 1.2%. In Saudi Arabia, much will depend on how much of the oil windfall revenue gets spent by the government. In the extreme case, if it is all spent, non -oil real GDP growth could increase by nearly 1pp. Colombia is expected to see a 0.6pp pickup in growth due to invest ment in the oil and gas sector. Over in Asia, Malaysia is a rare beneficiary, though net exports of LNG (2.9% of GDP) are much larger than those of oil (0.6% of GDP).